Infamy

A famous rapper's last refuge

A couple of months ago, I attended Solange Knowles’s Glory to Glory on a Sunday evening in Los Angeles. She’d curated a three-night series of large-scale events at the city’s Disney Concert Hall, with the finale being a survey of black praise music across genres and emotional territories, from jazz-centered and reticent to southern gothic organ playing, to the effusive revivalism born in black pentecostal churches. The offering was thoughtful and thorough and it felt like a black bourgeoisie who’s-who in the hall, a bunk catharsis too ostentatious and classist to slip into, but with some gorgeous music and the enduring questions, who can afford both financially and spiritually, our repackaged real black experiences when we deliver them in big-budget venues, who is it for? I’m always glad to see artists paid, whether through institutional bureaucracy or the old fashioned cut of the door and bar way, but whose glories is this pendulum swinging between and are those of us in attendance some self-appointed talented tenth flexing our nearness to God and the Devil with equal esteem for both? I left in that satisfied turmoil.

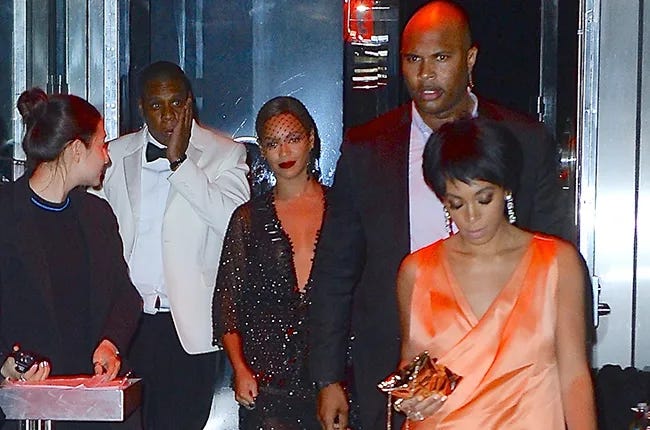

During the performance I was distracted both by and into this self-interrogation because directly across from me sat Beyoncé and her husband Jay Z. I joked to my friend, he came to be saved, we’re in a staged church with the antichrist. He seemed hyper-vigilant with a wind-up smile, and Bey appeared cloaked in his demeanor hoping to be invisible and let her sister shine. I thought of the famous photograph of the three of them and their security guard Julius leaving a hotel after a discrete/indiscrete altercation in the elevator between Jay and Solange, when Solange joined them to talk during intermission, between acts of glory. In the photo, Solange had punched Jay, and she walked in front eyes downcast like a modest champion, while he held his jaw in shock, smote, but almost impressed— maybe he hadn’t been surprised in a while and was grateful that his sister-in-law was brave enough to take him there, into the unexpected. Here and now, bygones seemed to be bygones, that incident, though as immortal as Christ consciousness, was a long time ago (2014) especially in celebrity and media-training time. Optics construe their own ancient and timeless clock. But I’m always secretly rooting for Solange’s subterfuge and the version of Bey smiling goofily and muted in the open secret, but with clear though tentative pride. An untold story that tells itself. Scene.

—

My inner vigilante is sleeping or sneaking away just in time to allow me to see past what I’m trained to notice and into the heart of the lion we’re all about to eat, together. The lion is ourselves and our idols, our ego and theirs, withering into parody, sobering up after an infatuation that lasted so long you called it love for comfort in your judgement, which was poor, provoked more by flattery than passion or real feeling.

I’ve been enveloped in the lore of black music all my life, cloaked in my own way in its magic and disgrace, but as it loses its gleam I start to realize it’s been hindering me, tempting me toward the wrong kind of love, like a harness I wore so I wouldn’t have to fly on my own above the graveyard of dead or lethal legends. I’ve read so many biographies of black men and women who make music, and whenever they do something questionable in the abstract, in a book, I cheer and investigate where that betrayal made the music more guileless and sincere. My neutral karma was I’d already lived through it, the contradictions, now cliché to me, of a man who can write gorgeous gold-record love songs and beat his wives on the side. It’s been like tradition, rite of passage, sad bliss of making it to the family you asked to be born into like getting into a terrible club where the best music is playing. That was my father. And I loved him anyways. I’d fall in love with men like him but less severe and in my own aberration find those men lacking— in guns, in genius, in struggle, in robinhooding evil.

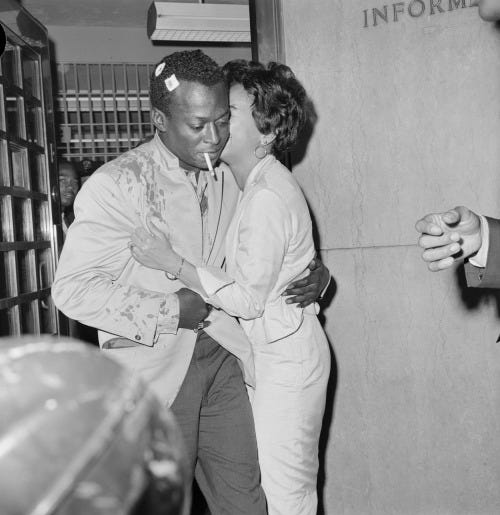

But I was reading about jazz and soul music, sometimes gospel or ambient or tropicalia, I was from or partial to those traditions. The men died young and broke, signed shady contracts they couldn’t read, or got too close to the sun and were killed, all besides Miles Davis it seemed, couldn’t get an image together. And Miles is in the muse’s eternal purgatory, his tongue is in my mouth, Arthur Jafa’s mouth, Don Cheadle’s, Cicely Tyson’s, Amiri Baraka’s, he cannot escape, and he confessed his evil on the record, in the books, to his victims, is why he’s easier to love. Sanctimony is so ugly its dysmorphic nature bleeds into one’s own style and ruins and stiffens it and gives the music rigor mortis. Looser and with less abjection and loss to obscure because he grew up wealthy, son of a dentist in East St. Louis, Miles didn’t just teach cool, he taught us how a successful, unfazeable black man should walk, look, dress, love, fuck, leave. He even made abandonment and recklessness pretty. Because no one could keep up, he’s a kinetic brass monument, not just a muse, he is the one who would have been in that room with us on some Hollywood Afrikan Sunday, dressed so well he or we became invisible, walking through walls and glass skies into an elite or elevation beyond color, entitlement that was black and studied nothing but itself. When he was photographed after having been beaten by police outside of his own gig at Birdland, Miles was laid back, intact, stoic. His wife Francis on his arm, so in love. You can spot a hint of vengeance in the way he held her and kept his blood-soaked coat on for evidence, leaving the courthouse to the silent paces of “Kind of Blue.” Barely blue, all black to you. He had inherited black privilege and a soul. He wasn’t tacky, when he was it worked, just as well as his overt cruelty did, just as well as his perfectly pitched compositions, just as well as when he put his soul on ice to scream backwards. He loved music more than he loved his image is maybe why, he just wrote his image into his sound.

Why doesn’t this work as well when hip hop musicians do it? Very few become muses and I’m straying and moving through tangents because my intended subject is Jay Z and he is no muse of mine. I’ve never even really been a huge fan though I recognize his contributions. The caustic tone of his voice and his verses about rape and ‘eat the cake Annie Mae’ have always stood out more to me than his triumphs or verbal dexterity. When he leans into meanness it feels like he’s just being himself, when he uses silence to control his image it feels like covert rage could swarm at any moment, mania might help, but if he possess any he hides it. He prides himself on scolding manic peers like Ye. But I don’t subscribe to black excellence™ or Roc Nation brunch excellence because of what I’ve already said about sanctimony being a very hideous form of gainsaying and praise. All that is a sanctimonious and vapid display of yes-we-can opulence. What are they even talking about at those toasts? Diddy is the master of ceremonies. Didn’t they invent and proclaim their own excellence, where else does it live besides in their minds and delusions of fanatics? What is it alibi for? Who is it helping?

This week, as anticipated based on the decades-long and very public friendship between Diddy and Jay Z, Jay Z was named in a case alongside Diddy, accusing both men of raping a 13-year-old girl at an MTV music awards afterparty in the year 2000. Very retro, very troubling, not surprising. The attorney, Tony Buzbee, whose name sounds mythic and qwackish, is in fact very serious and well-regarded. So that what did surprise and motivate some of us to clutch something the way Jay Z did his jaw outside that hotel all those years back, was his response. Instead of silence and sending lawyers, he wrote an indignant 3 AM style letter about how heinous the case’s claims are, never claiming innocence, calling the attorney a charlatan, and promising he won’t cede ‘one red penny’ to claimants. The letter ends in pure self-important farce: I look forward to showing you how different I am.

Is this the pride before the fall? A pride of lions, would we eat our own aching hearts to maintain our kingdom, our reputations? It’s a strange moment for the man of the hour to chose self-sabotage, so strange it feels involuntary and somehow humanizes him and takes him away from the machines he’s been conducting at the black excellence factory, maybe to his detriment. It’s a strange time to remind us, as he does in his letter, that he’s a young man (just turned fifty-five, ‘from a project in Brooklyn’). Because the Internet never sleeps, the backlash against his proposed youth and naivté was instant, replete with reminders that he sold drugs to his own mother and shot his own brother while growing up in that project. How do the born ruthless rehabilitate? Who signed off on that letter’s publication? Likely his worst enemies. Is the CEO of Roc Nation a federal informant? Why is Jay in court with a man who claims to be his son refusing a paternity test, and trying to ensure gag orders? Why did he attend his twelve year old daughter’s first movie premier the day after publishing this uncharacteristic letter online, and smile on the red carpet while throwing double- peace signs in the air? The unexpected is refreshing because we know it’s inevitable but can’t always predict how or when it will arrive and reveal its power to alter destinies. Our eyes lean up.

Something is amiss, except it isn’t because we know the jig is up, the “Jiggaman” is. Rap is dead. Jazz lives. I think to myself often. And why is rap dying young (fifty five isn’t young for a living man but it’s young for a dead one)? Perhaps it’s got too many rivals, itself among them. The black masculinity in music, really brought forth by Miles, if there is any lasting template for it, did require wealth and elegant reserve, luxury and leisure, and maybe even drugs and women, a certain expendability of resources, even of its own producers and emcees, who are all threatened with planned obsolescence, so that the faux-regal culture they glorified was their built in assassin.

The black classic depravity had to be smart and appear ethical and consenting; it had to come from money not come to it roaring and doing anything from investing in prisons to cheering for capitalism to keep it. It had to play instruments, be trained, it was elitist, it couldn’t retire and become a stodgy mogul who owned his friends’ masters and sold them off to strangers. Something is terribly wrong and the songs we used to chant to and learn by heart are now shredded confetti dna evidence for the coming federal and civil trials of the incriminated. And their sound, unlike other sounds of love and oblivion from Sam Cooke (who was killed sixty years ago yesterday) to Miles, to my father— the rap songs cannot scrub the rap image from themselves, as we listen closer they become more incriminating, diaries of shame and shamelessness that taught a lot of now-grown men how to live wrong and embrace it and brag about it, and get us whom it might affect the most to condone it and celebrate it and desire it as lover or favorite black archetype. No more.

The ruins here cannot even be fetishized and resurrected clean; this is a time of mercy killing like in the end of Their Eyes were Watching God, where we have to decide to pull the trigger, finish the vivisection, or become heartless and soulless enough to live with and uphold and be at the mercy of a culture that wants us dead, victimized, optimized, eating its stale cake in silence. There’s no room for clemency or romanticism, and though money and status might help the accused win back social favor over time, or at least flee to another country like Russell Simmons did to live out their days, we will never be able to relish music that outlines abuse, motive for it, love and glorification of it, and the promise that they’ll do it again and pass it down and protect and serve one another over their women and children who are pawns in it. Fifty years of black culture are on trial, all of us are. I kidna wanna walk away like Miles did and never speak of it, wear my own pretty things and make my own pretty music while they break, but even that, part of my inheritance I sometimes claim, feels irresponsible or just silly. We used to have the freedom to be more playful about transgressions, now it seems the lives of children not unlike myself growing up but many less lucky, are trafficked through the music and therefore through our silence about its abuses of power, how the industry is built on the trauma of black life and therefore needs to reinvent it to survive. Victims of this system are on social media platforms begging to be heard, calling themselves Jane Doe one day and on national television another. I am listening in stunned silence and it feels like mindless fans who refuse to acknowledge how it’s all unraveling are the real conspiracy now.

And since Kendrick Lamar’s beef with Drake is in part due to Drake’s treatment of underaged girls, if these new allegations come true like awful dreams often do if you make the mistake of letting yourself have and respond to them, will he pull out of the Super Bowl, will he extend his beef to his employer for that gig? Opportunism and selective punishment plague us all, that’s how we get to open, unabated genocide, open sexual assault rap karaoke, open riding for these rituals just by abiding their basic daily code: say nothing til you hear from… who? But when does it end, when do words and sounds get to be restored to substance, when do those who either keep quiet or deny they ever did anything lawless to harm others repent so we don’t have to think about them, for them. And if it’s not true that the implicated did crimes, do they care that someone did, at their afterparty, to a teenaged girl who a limousine driver allegedly scouted because she was Diddy’s type. Who will be left crying outside of the club now, we want to know, we need to decide. Rap has no Miles Davis, no prince of darkness, so that its jesters of false light are falling on top of those who love them now and it ends in ballads but these men can’t sing—

I think about a time when I will be relaxed.

When the flames of non-specific passions will wear themselves

Away. And my eyes and hands and mind can turn

And soften, and my songs will be softer,

And lightly weight the air.1

from a poem by Amiri Baraka called “Three Modes of History and Culture.”

Damn, Harmony 👏🏽👏🏽👏🏽

Incredible writing. I am struck how it made me view the intersection of art and capitalism. How rap went through a phase where white suburban kids were its largest number of paid listeners.

A system that attempts to capitalize on everything will pardon most things done as long as you end up on top.

The internal contradictions of misogynistic lyrics and a beat appear to transcend the initial feigned indignation to the lyrics because the beat moved us. But at what price? Authenticity of creating and receiving music became lost in the landscape of how to make more money. We now wallow in the mire of ultra-processed products that contribute to malignancies because that’s the diet we’re fed and tastes good.