I thought we had a nice space to think in

Meditations on the reprise of David Hammons' Concerto in Black and Blue, the spirit of Roberta Flack, the blues themselves

In my hand, a glowing glass rectangle in a jacket of rubber and agate. I’m told it must be stowed in a light-blocking sac, locked there as a minor penalty for a life of obliging avoidable distractions, if I want to enter the Concerto. I want to enter the concerto. I want to become the concerto and allow it enter me like Polystyrene’s mischievous simplicity when she yells I-dentity!

My whole identity is on that machine, I’ve heard people, sobbing to confidants, after misplacing a cellular device. I surrender the phone, my whole identity is on me now. We’re given stubs of indigo LED light powered by the pressure and release of our fingers, which is powered by the pleasure in our hearts, reckless blood, hushed obedience to what the vault called the body asks of us in a room burdened by silence. We enter a room so dark we have to use them or stumble and be still. Impromptu seance meets amusement park ride jitters and blurs darkness with rebirth, danger, and the blunt thrill of uninvited revelations. The belly of the heart is blue. The belly of the beast is— too. Belly’s bluing: fight scene, flight scene, love scene, sex scene, blood’s sheen, preemptive happy ending to a pitiful, predictable story about hustlers who learn to read in the revolutionary theater, and repent for lives of crime with the rudimentary and perfect militancy of convicts. Commissary blue, policy blue, blue pills appalled as they stain the tongue with liar hunger, you don’t have the blues, you want to buy some, movie star blue, Louisiana Purchase blue, the blue green of edemic ankles near Van Gogh’s Water Lilies, culinary blue number seven in a vat of sugar or quicksand.

Singing the word blue is great luck for contented losers trapped between the devil and the deep blue sea, those abandoned by both evil and virtue signals and forced to combine them and make an American. The 3AM commotion blue, the Guinea blue on Amiri Baraka’s Kente cloth tucked into his dress shirt like a noose or night bird, the seeped-in barren blue a black man’s eyes turn when cholesterol gets trapped in pupils and makes a curtain for lack of sun to metabolize it back into bronze. The pitch/black in this Concerto quickens my attraction to the unseen aspects of ourselves and I think of Jimmy Baldwin, walking methodically into the ocean in Spain late one night, circa the late 1960s, pandering to his depression before it became rage or resignation, voguing for death like its best descendant. He was reacquainted with his human ego just in time to resist the indulgence, the drama of his near-undoing then thwarted by what if I miss the pain of existence when I shed it or recover from earth? He blamed love, but there were deeper wounds that made romantic love a scapegoat for less glamorous devastations. The true creative spirit is born blue and needs a secret cellar to ruminate and deepen through, a sanctuary where the blue can possess us and we can respond not as professionals but as witnesses and students, asking bittersweet questions of robots and oceans and training them to reconsider integrating their souls into the mechanical revolution.

David Hammons composed the definitive blue-blank concerto of the unspeakable, unremarkable, unrelenting moment when the subterranean catacombs of our minds will become the final refuge ahead of nature. This is a post 9/11 endeavor (it debuted at New York’s Ace Gallery in 2002); it predicts time stalling in a blue ravine, gasping azure, groping at graffitied tunnel walls in search of its name as directions to somewhere familiar, some blueblooded hushed-oracular place of asylum where the music of tiptoeing in the dark inserts itself, and is both so evasive and so confrontational that it stalemates and that’s the end of the world as you know it, the current that takes you under on behalf of your own will.

The bull and the snake circling one another in the dark mass that the bull is and transcends, that the serpent poisons with its bright horizon. As the room gets more crowded, the brightness accumulates in excess and breaches the sanctuary until it’s a dangerous carnival that might abduct and puppet your shadow. A moment ago you spoke to god, now you’re intruding on his silent crucifixion. Disaster does play out that ambivalently and all of sudden what you thought was saving you takes you underneath its veneer to suffocate and be disillusioned. Some can’t stop making doomsday a punchline, others can’t stop singing to it and negotiating with trouble for one last glimpse at beauty, at the blues it might induce once more. I think, while inside and before the crowd is too much, when it’s just me and my friends, that even they might access a minor hysteria and pounce on their own shadows giggling, grieving their substance. I think that I’d like more time in this booth and bath of light and shadow, that I need the experience to last like the spillover from a former confession of taboo acts you no longer regret. Then I realize, in a detached way, that a maniac with a weapon could hack into this room and massacre us, that this is where we’d hide if a maniac with a weapon had hacked into our waking lives and tried to massacre us, that no one in this room is being traced as well as those outside of it. The remedy and the threat are one. Blues music, blues people, phat blue sun attached to our hands like prison numbers. These is our final moments of anonymity. Enter data breach blue, true Mississippi Delta blues. And we use them wisely, skipping in the dark like the lost children we are.

—

David Hammons shares a birthday with my father, July 24th—different years. My dad was born in 1934, Hammons in 1943. Nonetheless, a couple of months ago, a sudden affinity to Hammons’ work consumed me for a week, then recused itself. He appeared in my periphery like a distant relative seeking reunion might, lurking, lingering until I looked outside myself and noticed. His ability to be overtly suspicious of the business that pays him, to try and topple it from within only to find himself on the mountain top as its sovereign, is miraculous and relatable. He goes on the record announcing his disdain for the artworld and the fetish objects called artworks that are sold on markets like sad descheduled drugs, then, in revolving acts of masochism, he presents his own such works in galleries and museums, exhibiting allegiance to what he finds oppressive or pedantic. And while the self-conscious high concepts of many grow contrived and done-already, his maintain an aura of inevitability, as if he is fleshing out aspects of divine architecture that were always meant to surface through him, calling us silly for missing them before he arrived. Hammons realizes the dormant dreams of my father and all madmen, to survive in incoherence, to never have to appear in literal translation. The pitfall, which is more of a vat of despair waiting to be experienced at the end of their shattered rainbow, is that the audience for these rebellions will reintroduce you everything they rebel against with the same prismatic force. No fugitives get to live merrily in the center of the panopticon Bourgeois fans with unassailably eclectic tastes will praise someone like Hammons all his life, which they call a career, though he still aims to make it a life, and gatekeep him like you might a poem written only for you, so that he’s off limits, too offbeat, and eventually too expensive for the working class black tradition that helped form his consciousness. He becomes a ward of prestige, a nomad even when at home, a show piece. He might not have any pop songs that offer themselves up like Karaoke sluts to anyone who comes across them, but his strange haunted medlies are the monsters that make the pop songs necessary comforts. The popular songs my father penned and succumbed to land him in a similar predicament except they reach more people and are easier to reproduce so that bonafine elitists will find him too accessible and leave him alone where he can pursue his incoherence privately. Are these the only two options for the so-called black artist, is a question I ask again and again. Both roles are doomed and revolve around one another like binary stars, the popular and the avant-garde using one another to deflect from their own loopholes as if either is a pure and sustainable category or attached to an artist’s desire to communicate, to be engaged, and to earn a living. Hammons’ Concerto is how I imagine I’d have felt at my father’s funeral had I attended, like a passenger and an intruder and not there and never leaving.

1—

If you can survive popularity and hype in any area of the arts, you’ve survived an apocalypse, a pox on your soul called success. I exit the concerto and the end of the rainbow is without sweet relief. We get our phones back, a docent has to unlock their rubber cages. They land in our palms where the blue lights had been, emitting a fainter and more insidious cerulean. Our conversations are about whales and longing. Did you hear about the man who was swallowed by a whale and spit out unscathed just last week? I ask, rhetorically. It doesn’t matter if you heard about him, we just simulated his experience on land. He too seemed tempered and cured by a silly theoretical proximity to ego death or eternity in blue. We now know how we’ll move about when the cities collapse and we have to burrow through their bones as broken machines flicker and scream in us.

Someone asks: Is this it? On the inside, like she’s volunteering to be the first character killed in a horror movie. David Hammons’ work is usually very deep, she continues. Should we tell her? Does she know her subconscious is captive, that he’s captured it and outed her entitlement to the black tap dancer giving her something spectacular and distracting to marvel at— a black genius pet who is so very interesting and special she grows possessive over him, and expects him to replicate the same sequence in new variations any time she’s visits, and keep away in the interim, keep busy rehearsing. Sit, stay, she might as well be saying. In this concerto we fidget and reorient ourselves to the sacred-mundane. We’re taught that if it all disappears the beast will keep us inside of it as its hidden cameras. We’re reminded of that black dadaism/nihilism of being too visible and invisible at the same time, all the time, spies, because we refuse to be a victims of such dumb circumstances, a refusal I inherit from my father, David Hammons, and everyone undercover, in drag, being dragged, dragging you back home, winning at it, discovering there’s no prize but drastic alienation. It was a beautiful Tuesday. The tension between bourgeois houses of worship called museums and galleries and I wanted to do hoodrat stuff with my friends was mounting and it’s not hard for me to convince myself that a few artists anticipated this and made its articulation possible in advance, to topple the machine handling you and in your hand.

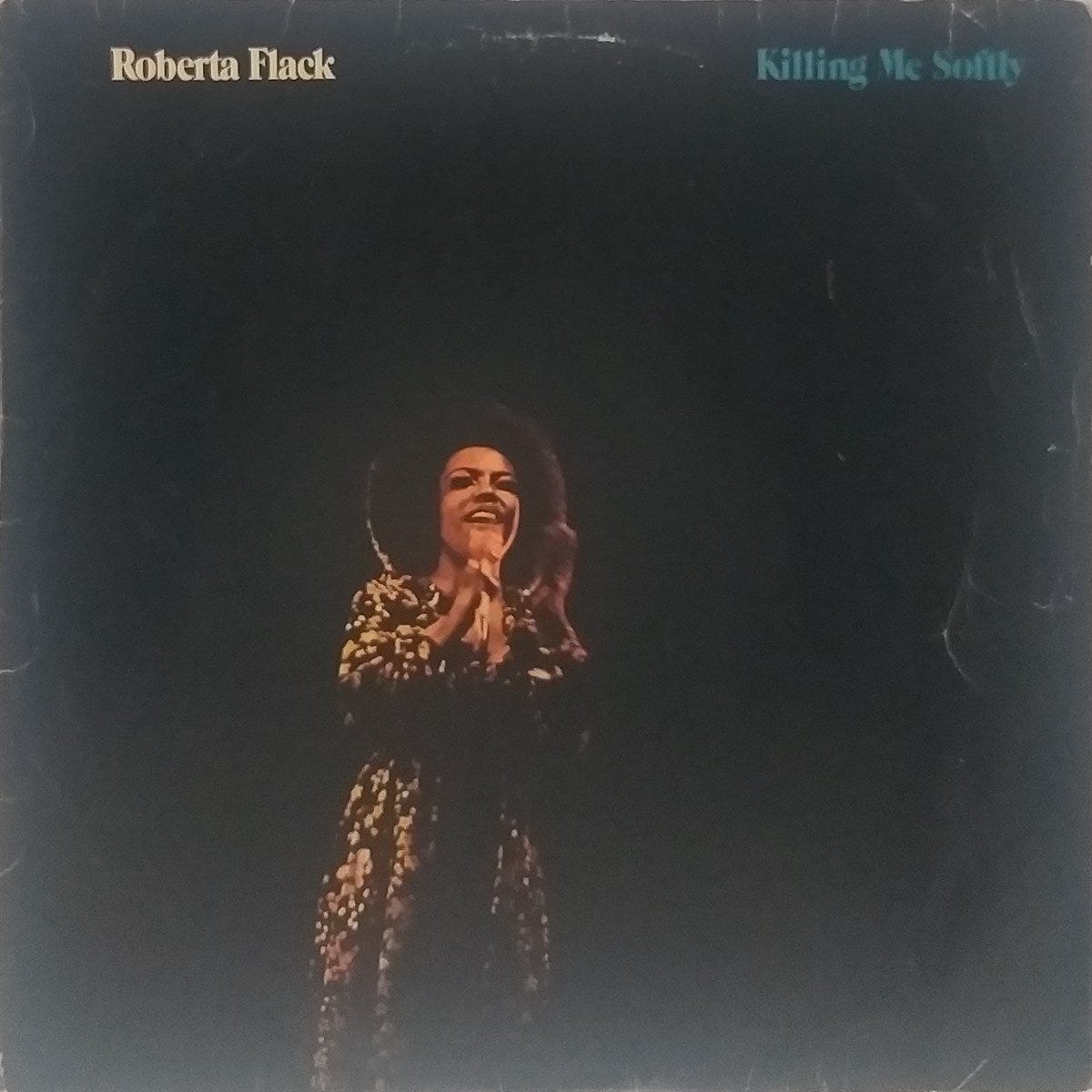

A week later Roberta Flack died. It’s her voice that could have animated and oriented Hammons’ Concerto with specific ghosts. Her tone is so close to disembodied that it subsumes when you realize its sincerity and physicality. Sing a song of sad young men, she begins her “Ballad, of the Sad Young Men,” … all the news is bad young men/kiss your dreams goodbye. If the Concerto in Black and Blue is their tomb, her anthem is their requiem. All the sad young men/choking on their youth/trying to be brave/running from the truth. By the end of it we discover their martyr, a girl always trying to cheer them up and wrest them from some dark, shapeless, brooding addiction. I left the gallery more intent on refusing the role of comfort girl, a thankless supporting role about harboring unconditional empathy for those who would leave you in the belly of the whale, or did, and then acted nervous when you emerged unscathed and a little giddy, angel of rebirth cycles overcoming the angel of death and haunting it forever. She’ll haunt us forever, she who could address the blues men with such tenderness they gain vicarious redemption through her. She who understands we’re in that room together, puncturing the darkness together, why not let intimacy be sweet there, instead of violating and frigid. We’ve mourned her in advance as we might a father or sacrificial lamb we want to avoid becoming.

At the end of mourning, when it’s still blue but the sun is prevailing, the lightness of a changed and recharged mind is enough. We don’t need to demand it to perform conflict, suffering, overcoming or preaching to prove what’s it’s come through, though if you know anything about the blues you know they sneak up on you as the the contents of a neglected region in your own mind and you’re lucky if they ever leave. Even when they do leave a part of you will always be asking: Is this it?

I hear the cadence, feel it's movement and rewind grounded.

"Sad Young Men" is one of her good ones; I really related to it.