Hell-bent

Black-eyed angels swarm with me: on a family picture I rediscovered this Thanksgiving

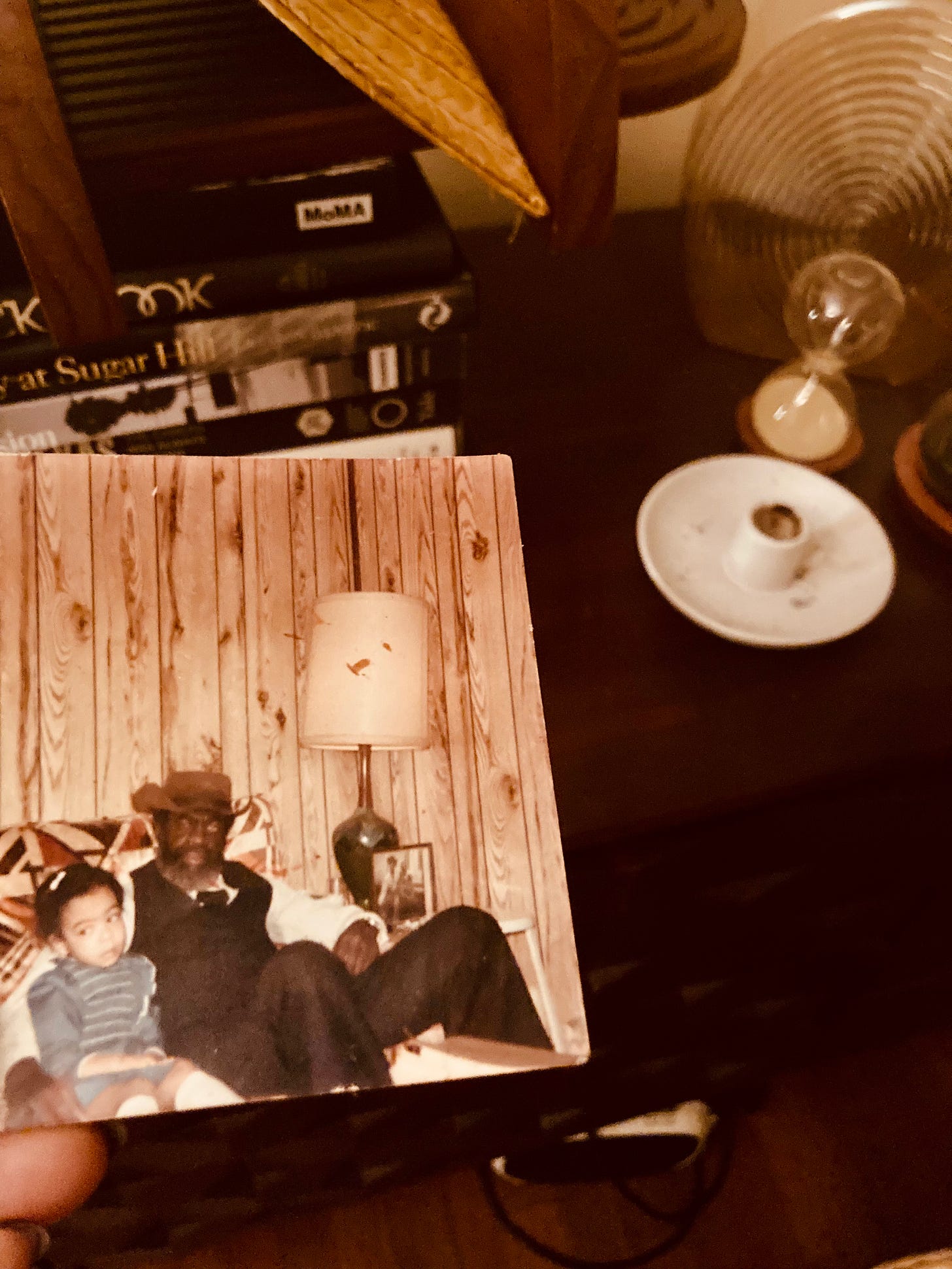

This photograph is the closest I came to attending my father’s funeral. Is it a photo, or an image of quiet damage and repair vaulted and venerable in my memory, aching and vulnerable in my reality, discovered again after I thought I thrown it away, this time hidden in a book on Miles Davis’s style that I removed from the shelf to browse absent-mindedly, improvising like my home is one of his haunted melodies. I opened to the photo and it spoke in my father’s voice, stern and sterling, never leaving. And I read a page about what Miles wore, what he took off, a shirt or a note, to make it his own, composing even in the way he held his body. We were like this, dad and I, held together and apart by meticulous attention to style, gesture, stance, recoil, the reckoning present or withheld in each of these details. There’s nothing I can remove from this scene that wouldn’t efface it and ruin it by hiding it from itself. An edit or crop would be a blindfold. It requires my father’s weary, steady eyes, squirming to liberate themselves from the skull and the target. And my worried, jilted eyes, praying how Kamau Brathwaite prays in litany at the end of a poem may he succeed, may he succeed, let him succeed. My tourniquet barrett is a necessary indication that effort was put into the unruly hair. His impeccable beard somehow managing to seem like an afterthought or organ of the body, is necessary to suggest succession, and me as the successor wondering what hidden duties might turn my averted gaze into leavers for easy leaving, an avatar for the girl who knows she will be abandoned again and again, as protection. Living for you is easy living, Billie Holiday croons, into the image where I play a young diplomat wondering if she’ll outrun the disasters she will inherit until they become music. Who would I have to trick into justice’s oppressive arms, what predictable future would I risk to accomplish this?

The will to adorn would always be on our side. Dad sports a resurrection scene wardrobe from the southern gothic tradition in the midwest, by way of Hollywood, the Stetson he would have been buried in if he’d had any say, let’s say he was sent down in his favorite garment, with his favorite gun. I wasn’t there to refute it, I won’t fact-check with witnesses. I’ll imagine his head covered and entombed like a pharaoh's en route to mummification, roses braided in his deep-set, upset, eyes, his immortalized flesh shrouded and de-segregated in the cowboy’s felted crown. I’ll pretend my dad was coronated and prayed up before the grave, saved from his terrestrial trouble as it engraves him in scars and ladies of the flowers even now. And I’m a furtive notion in the parentheses of him struggling to lean past their borders and become black Baudlaire or the seraphic atmosphere of before I understood the body as failed wings crouching around a fire of blood and language to announce that it’s retrieving amplitude and altitude, that deteriorating is its final joke ahead of revival, its last and laziest angel.1

Dad used to sing the country blues, the hard time killing floor blues, the lovelorn blues, the broken and blue/broken and blue J Dilla turned into chant his too, the cover me blues, the where’s my money blues, the where’s my woman blues, the tell me how long this train’s been gone blues. Jimmy was blue, the belly of the beast was his fist or quick drawn .45. I was not yet 5 here at his homegoing practice, but found his immensity thrilling and anticipated the am I blue, you’d be too, we knew was soon to return from exile. It was like he saved the best part of himself for me in traces and trances like these. It was too romantic to grieve or survive without mythology and forgetting. So that the image now wrestles me into a place beneath and ahead of my understanding where I have to feel everything I’ve annexed to selective amnesia, and be brave in a way that is yields no comfort besides that of looking right into the camera when I dismiss it to rely on the spirit’s knowing.

The idea of being alive in a world without my co-star here might have offended me if he had really left, had I let him out of the myth and into the garden of incidents. As you can see, I am seated beside him, visiting him in his rehearsal casket, swapping instincts with a master-slave-master again, leaning toward casual exasperation and evidence of things not seen as they are happening, misshapen by reputation and rumor. Was I flinching or fawning, inching away or reenacting the line in the Iching about escaping love on purpose to be drawn nearer to it by chance or inevitability, or how wanderers, forbidden to drift apart, experiment with the myth of physical distance until they learn to embrace this destiny and share a grammar of domestic scenes that vanish and recur like theater actors entering and exiting through cellars and missives in a fixed plot. Was I afraid of him, or afraid of how much I loved him? Was I ambivalent about the meaning of childhood like I’ve mentioned before? I didn’t understand why he couldn’t transform right there, be a kid again, restored to the frequency of his spirit, why we couldn’t skip out and play and sing and soar. I didn’t comprehend how he had used his body to offer me mine, and worked himself to death, and never complained except through his violent outbursts, which were his renewed childhood, his inverted tears. His was a compulsion to transcend the Delta cotton for the mesh of microphones patched together with similar pick-me, take me desperation, tension. Coltrane’s Ascension was released the year my dad finally made in to Los Angeles, to the apex of industry, to spend his life writing forever into a script in the present tense, chasing circumstance down until it surrendered or killed itself off like a weak character who misreads his one pivotal line and runs off into the no-shine inconclusivity of supporting roles.

Birthright and funeral rites converge in the kinetic inertia of our best (most honest) picture. The interlocutor is criminality, a father and daughter being charged together, and assuming the irreverent servility of mug shot subjects. The camera is an intruder our skin lures and leverages for redemption, and we are reluctant witnesses to our own framing and acquittal. We both cherish being underestimated, an alibi so that we’re not seen as the flight risks we surely are, and pose together in limbo but not in fear. I’m leaning away like a trained fugitive, plotting ways to make my dissociation and boredom with pain resemble profound courage, to shroud my dead in glory by reminding them to give up their deaths for me, or fake them, and hand me what’s left to be done in the silence between these gimmick suicides— swelling yellows, a yearning so secret it mimics indifference and spares us. After posing with my dad at his very long still ongoing (as long as it takes to learn to mourn and elegize the living) funeral, what could I pursue but revenge in this code we’re given that lets us persuade one another to haunt loveless worlds with love. How could I not adore the sins of the father I’m told will visit me like his ghost and taint me and heal me? To have been his mercy and his downfall, to have forced him toward his endless sun. To have resembled co-conspirators awaiting conviction and bound by allegiance to one another. To have been charged. To have been released.

I would still wear that denim dress. He would still demand his suit and hat. We would still step out into the steepest most congested fog, weighed down by what others call loss and pain and trauma and disadvantage, and find it exhilarating, like an adventure we’d arranged for ourselves and hoped to disappear into. The part of me that never wanted to escape the moment or era this photograph captures, had to fake her death to get out, just yesterday, and again tomorrow, muttering you don’t know what love is, into a machine gun aimed at a lucky rabbit, she would carry his foot everywhere, his beat or beatings, her rhythm. The part of me that got out of the picture’s way so it could exist in another era sometimes trades the catch for a total collapse of timelines. Ye samples a song my dad wrote with Ray Charles and I realize the image of us is a sound woven and tangled and inescapable, a contract we signed in a field that came before our names did. In the break between paragraphs I’m told a story about Bill Cosby putting a cigar out on the genitals of a child at a private party made for such deeds (allegedly, hearsay). The version of me that escaped is rejoicing and weeping for the danger she saw as mere ideas of horror that would never catch her. If luck is an unsolicited secret retold to you over and over by those who don’t suspect you, of all people, of all the girls you’ve ever loved, might speak every language—I am the luckiest girl in the world.2

The voiceover is a one-take first attempt at trying this feature, which ended up being useful in editing. I didn’t take out that parts where I pause to correct grammar or word order, and the sound is imperfect, but that’s how I like a first take. I’ll continue to experiment with this when it feels appropriate.

For Giving Tuesday and the start of the holiday season all subscriptions are 20% off for the week. I’ll be leaning into archival, educational and exclusive content in the coming months as book projects and research intensify. I appreciate you reading and sticking around, I love it here.

Beautiful

💜💜