What is the Reason?

On the use of Earth Wind and Fire's "Reasons" in the film Killer of Sheep.

Of reasons, incentives, and motivations—we’re told the only valid ones are fear and love, though I would include greed and opportunism to account for some of the personality defects rampant these days, and maybe also dejection that goes on for so long it turns to evil or oblivion.

What is her incentive to search for her reflection in the lid of a pan and pat her head when she finds it, tending to every stray strand and letting beauty express itself through decency and understatement. Earth Wind and Fire’s “Reasons” (1975) as used in Charles Burnett’s Killer of Sheep may be the most poignant use of a song in a film. It wells up after the woman we know only as “Stan’s Wife” holds the stovetop close like a vanity or brace for the coming ache and wipes grease off of her brow. As she scrutinizes herself, we wonder at her reasons. She’s wearing her good dress this afternoon, figure-hugging but elegant, some eyeliner and lipstick, hair parted in the middle and pulled back into a low bun. She’s anxiously awaiting her husband’s return from slaughterhouse where he works. He’ll be covered in a faint residue of blood and guts, she’ll be pressed into her face by drugstore makeup. She she hopes there will be romance, but expects nothing. All of the sensuality and desirability the mainstream steals from people with real lives, real concerns, agency lifted from the consciousness of real working class people, takes revenge by increasing with each attempted erasure. You would rather be here in Watts keeping Stan’s Wife (played by Kaycee Moore) company, around the corner from Mingus, and Dexter Gordon, and Eric Dolphy, and the Dunbar Hotel— you’d rather spend time as voyeur here, than in any kitchen in all the world. The temperature is just right: impossible.

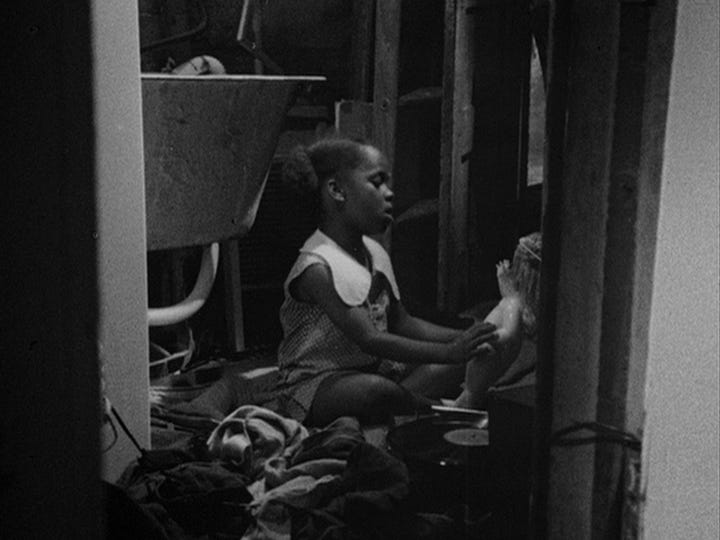

In the next room, her daughter starts clapping acapella as Philip Bailey’s voice enters through the radio ohhhh ohhhhh, like he’s about to tell on us for being ourselves. She’s playing with a naked white doll as she tunes into the music, reminding you the family is black. Their daughter is learning the polyrhythms of daily life in the USA, where we animate our mute idols with dances they would never quite understand. She’s surrounded by junk, a ghetto playroom, but it’s just her, her doll, and the music, a jazz trio. She knows all the tones and most of the words and she holds the doll at eye-level and serenades it reasons that we feel our feelings won’t/disappear. La la la la la la la. Her mom has gone from the kitchen to the bathroom to touch up her makeup, the song matches her restiveness with its spokes of shrill and shrug. All of the rooms are practically on top of one another so she walks to the other side of the wall to look in on her daughter playing. She marvels. The smiles they exchange are as bright and sure as the vocals, they declare total trust between mother and daughter and whatever spirit is coming through the doll. They are divining this afternoon, so that as the radio music reaches them, they use it as a portal, it nudges them deeper into their own spirits. This speechless, song-driven domestic interlude tells us more about the lives of mothers and daughters than any talking scene between them would. Theirs are the subtle gestures that make days bearable at home, when the radio takes over and the household falls into a trance together and the women there forget they are ladies in waiting, waiting for love to come in from outside. That love arrives first as a sound and acoustic condition, there is no lack as long as the song is playing, and the girl is playing, and the stove is containing the matriarch’s desire with metonymic warmth. Mother and daughter move like a song, accomplishing everything and nothing together.

It’s not reasons like logics here; it’s reasons like ultimatums, strict demands that are bored with themselves yet persist out of habit and necessity. These reasons are insufferable, too reasonable, too traditional— they are stark limitations. After a long day at work, Stan (her husband) might not have the energy to want her or make her his reason for coming home eager. He might overlook her effort to be nice to come home to. What he wants from the stove is food, not mirrors, and the song will be over by then anyways, gone along with the air of sweetness it encourages. By then the radio will be giving evening news, the rhythms of lazy afternoons replaced by the dry rhythms of duty and statistics, and their daughter will stop playing with her doll and ask to fed and bathed and put to bed, and the extended family will show up asking to hold some money for the week or looking to run a scheme to get some new money. All Stan’s wife will be is a mother by then, not a woman or a reason or beautiful. She’ll be the anchor that gives all the chaos of dusk its tidy resting place. She’ll satisfy everyone’s appetite but her own.

Psychologically, the secret thrill of the “Reasons” interlude is that this soon-to-be only-mother is stepping out of her usual role, in her mind, preparing to break with custom, surprise herself, or even try on madness for attention. She is weary of the routine, of being a platonic sidekick who is there to make her man’s weariness more bearable for him, to make him feel like a man, never flaunting her own needs. What is the reason women can maintain decorum for years and then one day, wake up, put on some different lipstick, and unleash all the pent up vengeance of a lifetime on its catalysts, who we invent. It is the self that is always the real cause of this switch, the self fearing its shadow so basking in the shadows of others and pretending to take care of and save them until we cannot ignore ourselves any longer and— snap! Turn the radio on for a fresh alibi and there is this falsettoed ode to remaining unreasonably committed to our most persistent fears until we transform them into love. I’m in the wrong place to be real, the song taunts.

What we’d notice first about this scene, if we were afraid of unadorned beauty, is that this family is poor, the kitchen is modest, the bathroom is cramped, the playroom is a mess, the house dress is dingy, and the doll has no outfits. Love inspires us notice the music, the wealth of happenstance that is the radio, the electric nourishment of black radio music coming through like the lightrays of golden hour and turning all of the drab details luxurious. The woman is gorgeous, the daughter, impossibly cute, her lyric retention, impeccable, the man they wait for, devoted to them, the smallness of the house, a demand for intimacy and reckoning within all of the potential of their bonds and clashes. The wife’s loneliness is not tragic or inevitable, but it does mark the love she shares with her husband in that she also shares in the alienation of his daily labor through her sense of being alienated at home.

Killer of Sheep is enigmatic in that you can love everything about its atmosphere without wanting to be like any of the characters; there’s no real hero and no idealism is coming to rescue anyone from their struggle here. Instead, you come out of the world of the film in sync with a methodical stillness, a longed-for slow pace that it fulfills, a reminder of your own reasons for interacting—these people know that anything presumptuous enough to act like it can save you from yourself or your surroundings, is a chimera. Daily rituals and small moments have to sustain you. You can’t spend life hoping to break loose and become someone other than who you are, or waiting for a new context to supply a better attitude. Life’s joy is now, mingled with everything bleak and messy that now always offers: now is the reasons. Kill the idea of tomorrow coming to extract you from the freedom of this endless succession of nows. Kill the sheep in you.

The limboing interlude where “Reasons” intervenes is everyone’s big chance to live in the moment, and it fades when the song fades. We’re just a parade, all the reasons start to fade. I’ve been the daughter and the woman here, but I’m left wanting to be the song as it forces pain, play, and anticipation to have an impromptu afternoon seance, or glance of a seance. Whatever happens outside “Reasons” is imbued with its cadence and chased into its light. If you’ve ever been nostalgic for a moment as it’s happening, then you’ve lived this scene. Sometimes I wonder if every moment that doesn’t feel like “Reasons” in this way is a disaster.

Omg this is incredible. I know it’s weird, but I actually discovered Reasons watching Killer of Sheep (despite having loved Earth Wind and Fire for a long time) back in Spring. I remember because it was still cold. When I saw the daughter singing along the song got me immediately. I found it with sh*z**m and I swear I listened to it 10 times back to back. I’ve basically been listening to it nonstop since. On Friday night I was in Chicago and I met a magnetic couple on the platform (in love magnetism—they themselves had met each other on a platform one week before) and ended up spending the whole night riding around on the trains with them smoking and drinking and eating chips. The train eventually stopped and the lights went off (Nathalie said she’d never known that in in all her life in the city) and we listened to Reasons and the lights came back on, and we sung every word and every little note just like the daughter. I love that song toooo much. Shout out to Jason and Nathalie ❤️

you’ve done it again 🖤