Jutting, sphinxed, like a limbless panther about to venture toward her kill and dress its phantom wounds, Cicely Tyson’s sullen and intent profile on the cover of Miles Davis’s Sorcerer (1967), possesses all of the duality of sorcery itself. Sorcery is magic so powerful it might fall victim to its own backlash, returning the spell to the one who casts it. It’s effortless manipulation of energies that impersonates the gods that way, in a perceived nonchalance about great feats, even while still being subject to unseen forces by which true gods are incorruptible. Dark magic, bruised magician, and ceremonial chaos are the sorcerer's realm of influence, her comfort zone is where most suffer, squirm, or scream uncle. Soft pink bubble letters combed through a blurry low afro reveal this album’s title, but Cicely makes the word incidental, bucks it with embodiment and begs the question—do we need terminology and names for mannerisms and acts when there are people whose presence surpasses their definitions, even undermines the essence of words by proving how many we lack and how we wilt the invisible with inadequate descriptions of it. This photograph, this neck exposed to its own critical urgency, could only exist in association with music, with kinetic energy. When Miles married Cicely after years of off-and-on dating, he mentioned in one interview that he thought she was a strong black woman, as if his decision to take her as his wife was rooted in pragmatism, in the fact that it was the noble thing to do.

The other dutifully noble deed was putting each of his wives on an album cover. At a time when record labels pushed for the images of white women on those record sleeves, he demanded the autobiographical, often cryptic images of wives and lovers, photographs that straddle horror and austerity rather than selling audiences a happily ever after that cannot be found in the music or in the romances that veneer it. Another synonym for sorcery is enchantment, that feeling of being under a sweet singing love spell. This album with most of its compositions written by saxophonist Wayne Shorter and featuring Herbie Hancock on piano, Ron Carter on bass, Tony Williams, drums, and Miles, does attempt to shred its own seams with the low flung levity of enchanted love. It travels like one long song, each composition weaving into the next until “Masqualero,” where the piano violates the smoothness with sharp tense chords and a conversation between Hancock and Shorter imitates infatuation trying to evolve into real love, with the piano quieting to tip toe while the sax woos us back toward passion.

This is the soul of the Sorcerer in charge, somewhere between seduction and retreat. The bass enacts risk within the dynamic, supporting the seductive ranges and abandoning the others. Two almost-ballads follow, a denouement. And the album closes uncharacteristic, jarring, with an almost goofy panache infested song “Nothing Like You.” There’s singing here, show tune style barreling repetition of the nothing like you… nothing like you has ever been seen before. It’s unconvincing, clashes with Cicely’s dejected gaze on the cover and with the embellished love story we’ve heard for the 30 minutes prior. But its call to oblivion does end the magic, halt the atmosphere of sorcery, and diffuse it into a silly reverie like flipping a switch or turning the dial away from a secret radio frequency. One minute Cicely was the only visitor during Miles’ slump full of addiction, womanizing, and sulking, another she was yanking out his weave in retaliation for years of unrequited patience and some physical abuse. Whatever sorcery ensued between frequencies they kept to themselves. Icons tend to both attract and repel one another, the space of passion too taut to accommodate both at the same time, but their temptation to try is urged on as if by dark magic.

—

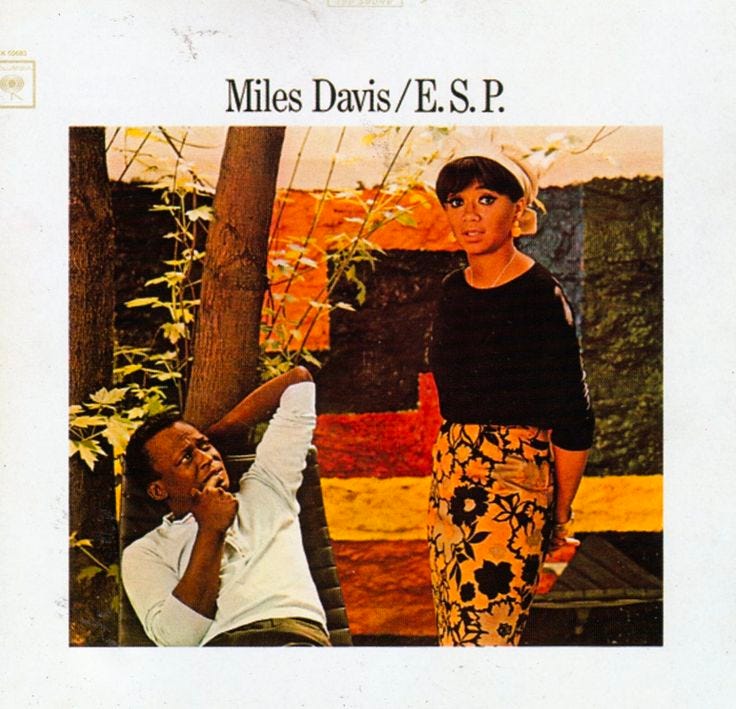

Here lived two entreaties and failed covenant. This album cover for E.S.P. (1965) documents not just the feel of the music on the album but also the final hours of Miles Davis and Francis Taylor’s marriage. He retains some machismo in the way he positions his elbow and torso, arm hooked onto the back of a patio chair, as if he’s lounging, while his eyes gaze up at his wife full of a level of pain and remorse this stoical prince of cool rarely indulges publicly. Francis stands over him tentatively, enormously elegant, and held up by the scales of justice. She dodges his piercing gaze to look out at the world begging for help— help escaping this man’s spell of a confounding amalgam of tenderness of spirit and violent outbursts, and help resisting the call to break free. A part of her wants to remain the pious spouse, by his side unconditionally. There’s a love story in these two desperate sets of eyes, a tragic one. They have reached the moment when understanding why they have the dynamic they do isn’t enough to hold them in it, when Francis’s empathy for what Miles faces out in the world and brings home as rage or neglect, is waning, or becoming unbearable as it mounts. And Miles, addicted to his pain, a real masochist, doesn’t even look like he hopes to manipulate her back into his arms with charm. He’s biting his nail as if watching a thriller in her, as if all of his adrenaline is anchoring him into this voyeurism of his own life. He’s out of favors and romancing her won’t work, he looks like he needs a miracle and she’s his guardian angel, the only one who can grant or deny it. His arms are open and hers are woven behind her back as if hiding a fugitive letter or handcuffed there by her wits, which she has clearly collected even as knowing what she needs to do next frightens her into hesitation. These are souls that cannot help but compliment one another even in conflict, they look so right and so wrong together.

The tensions on this album are as swirling and erotic as the cover suggests, demands. And the telepathic conditioning of throbbing love charges its tone. It vacillates between insinuating hard bop materialism and undoing it with meditative passages that supersede what is called the avant-garde in jazz because they manage to evoke the cerebral without become obtuse or illegible. The tones hang and sway like southern willows, but chisel the focus into the spaces between notes, the unsaid and unsayable textures that make or break true love. This was one of Miles’s unique abilities, to suggest so much that you as a listener are forced to form the ideas he simply insinuates. It’s the devil’s way of telling you what you already think, the angel of mercy’s capacity to swoop in looking mean and save your soul.

“Mood,” for the way it broods without stopping its other duties, without being lazy in the midst of utter angst, is one of my favorite Miles Davis songs of all time. It sings to and for me, and knowing what rests behind the eyes of man and wife on the cover, I imagine it as Miles’s apology to Francis, and his attempt to repent without giving her an ultimatum, finally. He quivers on his trumpet but paves its smoothest road through that bevel and tremble. Herbie Hancock steals and hides from the spotlight in the sound, turning the piano keys into dancing feet that are so quizzical about their own motion they imprint it upon you as they go. The union achieved by this band, and especially by Herbie and Miles in a mood, in staggering unison, would displace any marriage. The music is too romantic to look outside of itself. Maybe that level of achievement in artistry is toxic in that it makes anything beyond it subject to elimination, setting up an impossible hierarchy of pleasure that turns traditional love into a liability. Maybe so.

Four years earlier, a much less tormented looking Francis demurred on the cover of Miles’s Someday My Prince Will Come, an album that sounds like the gates of a fairy tale swinging open, an interminable frolic scene built on the standard’s reputation of glee and glamor. By E.S.P. Those gates and scenic routes have narrowed their opening to a crevice of living memory, and will thud shut until some other angle of delight and beauty can pierce the wall of sound. The way Miles and Francis haunt one another openly haunts his sound during this period. Him turning her life as a principal dancer into a danger and mirage, forbidding her the fame that was her destiny, and her turning his womanizing into his deepest regret and self-sabotage, and the maudlin way he mentioned her as his ‘best’ wife, in several interviews, committing to that horrific triage some men attempt when they’ve hurt people they love, that impulse to project all of their guilt and remorse onto the one who mirrored possible redemption back to them. Only in the music can love be this erratic and perfect and complex without also being threatening, but the dream of being the exception is what keeps us writing and listening to songs about lives our alter-egos live.

Black Betty Davis entered this realm of divine covering in 1968, her visage splayed and doubled on the cover of Miles’s Filles de Kilimanjaro, with streaks of fire orbiting her like snakes. The splitting of self from self that she enacts so grippingly in the photograph, is matched in the music, which now turns toward the psychedelic so that the sound can hallucinate into a new level of lucidity that is at once ancient and evolutionary. Betty came in and suddenly Miles was wearing platforms, slick paisleys and bell bottoms, and demanding a collaboration with Jimi Hendrix. The way Francis taught him about how the dancing body might help him inhabit the sound in his head with more precision of feeling, Betty taught him that he could shake off stodgy notions of stylistic sophistication and be as hip and expansive as he was. Jazz didn’t need to take itself so seriously. He didn’t need to arrive at intensity in familiar ways when the world was entering a period of intense escapism after a decade of political struggle. Miles and Betty were married for a year, together for longer. He once said cruelly that he married her because she resembled Francis. That comment was likely revenge for the fact that the coolest man in the world had encountered a woman cooler than him. He seemed to admire her with a distant awe. With every new pillar of sound came a new wife or lover who helped Miles crystallize and surmount himself.

In the 1970s, artist Mati Klarwein would draw impossibly gorgeous chrome black goddesses onto the covers of Miles’s albums like Bitches Brew (1970) and Live Evil (1970), wedding everyone to apocalyptic fantasies and distancing from the constricted realism of the portraits on his past covers. His music was entering a territory beyond human, his sound had exceeded his biographical narrative and was exploring the collective subconscious and how it undermines identity itself.

The cover of Nefertiti (1967) breaks the conceit of muses and apparitions as our entrances into Miles’s music. Here he stands alone, and he can’t even stand up straight. He huddles like a winded athlete. He coils like a hunter both hiding behind and peeking around a massive tree as he spots his game. And the look of distraught witnessing in his eyes suggests that he will not chase after it this round, that the next phase of satisfaction will be contingent on stillness, vulnerability, and sacrifice. Miles’s wives were not martyrs or hysterical waifs, he chose women who challenged him and found ways to possess them beyond their own governing logic. But each of these three women managed to get out ahead of another possible fate— becoming the object given up to the gods in a ritual sacrifice delivered to appease them so they send him more music. I don’t think anyone who falls in love with Miles can withhold the expectation to be devastated, the expectation to uplifted. In each sound and image he reveals, rests a new archetype, and no one said the archetypes were friendly. They con their way into the consciousness using beauty and truth. They have to be a little cruel to tell you of these pleasures which come only when you awaken to the end of suffering and kill its archetypes. And they have to be a little generous to teach you the difference between unattainable and possessed.

Amazing amount of content on this topic, thanks.

Thank you for this lovely piece. An excerpt, somewhat related, from Wesley Brown's recent novella, "Blue in Green" (written from the perspective of Frances Taylor):

"A photograph of her and Miles was put on the cover of "Porgy and Bess," a shot of the two of them, seated, their faces hidden and little shown of the rest of their bodies. Miles composed the shot. He kept a firm grip on his trumpet, and her two fingers dangled near the valves. Her dress revealed a knee and part of her thigh. This was a first for Frances, to be involved in any aspect of his recordings. And she loved the result - at the time. After he hit her, she saw it differently. His grip around the valves looked like a fist, pulling the trumpet tightly against his stomach. She now noticed how her fingers barely touched the trumpet, showing tentativeness about getting any closer to something so much a part of him. Her presence in the photograph was all about him. She was a prop, an eye-catching teaser. The message was: you are my woman."

Very direct, but I actually received Brown's book (technically speculative fiction) as a long work of music criticism, reading into the unreadable. And there's so much there to analyze.