Duke Ellington’s music possesses a precise sonic chivalry; he courts and romances the whole world with the sound of his ideas. Charles Mingus heralded it “Duke Ellington’s Sound of Love'' and composed a song by that same name in 1974, the year Duke Ellington died— a requiem so reverent it’s part hologram, and when you listen you can see Ellington reassemble into a mist of purpose, royal and real as ever. This tribute is more poignant still because in 1953, Mingus was fired by Ellington after a brief stint with his orchestra, for getting into an altercation with the trombonist over a racial slur. To be fair, Mingus was not wrong to react to being called a terrible word, but the orchestra was no place for on-stage tantrums. Ellington was a professional, he cared about his reputation because it made his work possible. Mingus was asked politely, flatteringly, to leave, and rumored to be one of the only players Ellington ever fired to his face, like a father figure looking a rebellious heir in the heart. Mingus held onto Ellington’s tonal love and abdicated any grudge. Duke maintained the exacting chivalry of a leader effective enough to remind us how to love and console one another even amidst uproar.

I’ve declared 2022 The Year of Duke Ellington, Duke’s Year for short. On a linguistic level, the title honors its cavalcade of twos— duality, dueting, dueling, Duke Ellington. On an energetic level, the fantasy and romance that allow Ellington to sound chivalrous but not frivolous, and to inflect the grand with just enough of the solemn to shape our black and tan habitat into an autonomous ecosystem in which we can swing gleefully or lean dapper and severe into praise, refusing to get effusive—such are the versailities and romances this year demands. And romance cannot be pursued, it’s a sensibility one has to awaken to and privilege over all of the counterforces that aim to dull and scramble it. Romance is a looming presence, a condition as elemental as air or light that asks that the senses tune to it. It’s the opposite of crass yearning, which is an absence pledged to over and over again in unnatural fixation until lack is made realer than possibility. When romance is scarce, all manner of fraud can linger as compensation for the missing eagerness and bloom that romantic energy instantiates. Love without romance grows ashamed of itself and turns predictable. Trouble becomes bearable when we stop romanticizing disaster for lack of romance elsewhere in life. The Year of Duke Ellington is whimsical and sincere without being trite or corny, amorous without turning limp and doe-eyed in the face of its clear desires, open-hearted but not gullible, and intolerant of dialects that oversimplify our range of motion and emotion and narrow our best ideas into brands.

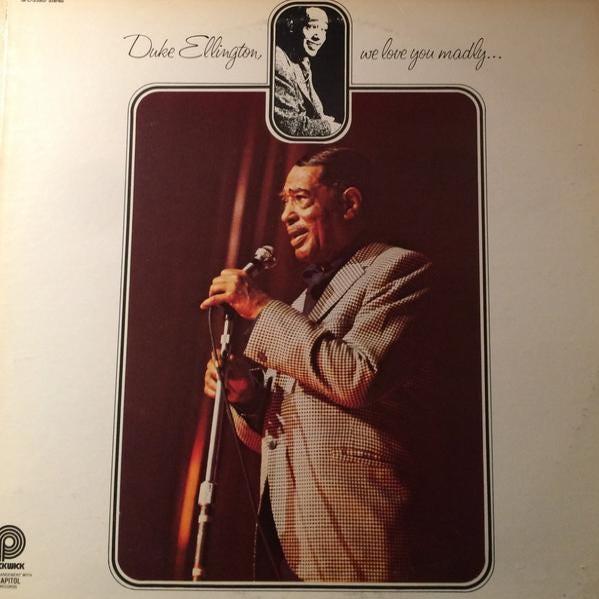

Society is a little desperate for a palatable new origin story, a renewed sense of purpose and direction, a myth superior to race and class categorizations— In the beginning was the sound and the sound was love and the love in the sound was Duke Ellington’s sound of love. Let it play. What can we restructure into resonance with this sound? Also in 1974, Miles Davis composed “He Loved Him Madly,” a thirty two minute dirge for Ellington, full of suspense, agony, and resolve. Spatially, it echoes his tribute to champion boxer Jack Johnson and therefore fittingly picks up on the fight and stamina in Ellington’s sound of love. Ellington’s was a lucky spirit, a winner’s spirit which made battle appear and sound effortless but never cowered in the face of it. In his grippingly hip and brisk tone, Ellington himself would often conclude interviews and live presentations for television or radio with the affirmation we do love you madly, flaunting his signature detached passion in a swooning cadence, not cool or haughty, too private for pompous dandyism, the phrase came out more like a humble bow. Submerged beneath his suave words and armored by them, lived a sensitivity that would account for ballads like “Solitude” and the way he would be moved to tears as a young boy when his mother played piano from sheet music. Duke’s sense of dignity kept that sensitivity in balance and allowed him to remain a fugitive from the kind of conflict that could lead to rage or unhinged malaise, while confronting potential threats to his purpose as a musician and composer with an easy scoff as he leapt beyond them. He sometimes seemed irritated when he felt misunderstood, but rarely to the point of condescending the offender. He deferred to joie de vivre when love was threatened, or became cryptic and quiet, as if scanning his mind for better sounds while giving you space to tune your own.

He maintained his orchestra for fifty years, while the post war shifts ended many an ambitious big band and traveling orchestra in the late 1940s, Ellington did not capitulate. He attributes some of his relentless drive to the fact that he wanted to hear his compositions played as quickly as he wrote them, by the musicians he liked best. We’re taught that leadership shows up in commitment to political movements exclusively, especially black masculine leadership, but what of the kind of leaders that Duke Ellington and Sun Ra were, turning collective improvisation into a new approach to family and to being, transmuting the loneliness and alienation caused by their genius by sharing it insistently, and giving their band members and audiences a sense of eternal belonging in sound. These displays of militant black romanticism are also leadership, and are just as harrowing and prone to infiltration that could dismantle them as any political movement. These leaders possessed a carnal need to make and perform music on a grand scale, and the way they lived as a result was explicitly revolutionary. The year of Duke Ellington is explicitly revolutionary. In 1987, Sun Ra offered his homage to Ellington in the form of a concert at New York venue The Bottom Line. The bootleg album documenting this event is dubbed Duke Ellington’s Sound of Space. The suite opens with Duke’s composition “Perdido” or lost, and closes with “Sophisticated Lady.” Of course Ra would equate space with love and update the formula of Ellington’s sound to accommodate the space age, echoing his own romantic musings about “Love in Outer Space.” Sun Ra’s Ellington is more ritualistic and jarring, reminding us that Ellington himself was responding to his industrialized urban environment, having been born in D.C. and based in Harlem. The sound of love speeds by you in a metro station or chills you in a damp alley beside the club, and then the sound of space gives you back to your imagination, these sounds need one another. Sun Ra begins lost and makes his way to that sophistication, that chivalry again, except in his version the chivalry is the act of being released from the terrestrial plane to roam interstellar and sure of oneself, like an afro satellite spinning and chanting.

While space is what Sun Ra deems sacred and liberating, for Ellington, the ultimate liberation arrives through faith, love’s dutiful accomplice. His Sacred Concerts demonstrate that approach to catharsis and the music that comes from them is unflinchingly content, and less restless and distracted by the weight of social responsibility than his other work. The Year of Duke Ellington finds us getting nearer to whatever we believe God is, whether that be spiritual or material, and therefore closer to home and more at home in ourselves and our expression of ourselves. In this way we banish reflexive cynicism, and understand that lack of faith in the future is not how we outsmart or overcome a complex and unfamiliar present. The opposite is true, we have to have the courage that iconoclasts like Ellington display, to believe in ourselves ravenously, selfishly, and to access love of the world through that commitment to our personal visions.

Ultimately, we reckon with our best artists after exit the flesh, picking them apart on every level until we’ve cannibalized them and undermined all that is most meaningful about their work, but I do not think we have reckoned with Duke Ellington or understood the magnitude of his contributions. He himself was understated and matter-of-fact as he went about his miraculous business. And now we need his sound of love more than most any sound available to us, most of the current sounds being redundant and cloying— blunt when they wish they were demure, uninformed when they believe themselves witty or slick, late while labeling themselves futuristic. You can detect those rare pillars of greatness because they never go out of style and are always arriving on time on their own terms, to the eternal return. They remain fresh even when their contemporaries sound worn out or silly in the modern context, and that acute endurance brings with it sharp flashes of romance in an otherwise drab and mechanistic sonic landscape. The rare ones teach us what it sounds like to fall in love with the same person or mood over and over. The Year of Duke Ellington insinuates triumphs of the heart that we’ve withheld previously for fear we might not deserve them or because we were too lazy to keep their pace. Now we have no choice, it’s either shift to a more pleasing and honest frequency or be overridden, devoured, and made obsolete by all of the smug fears we miscast as virtues. If love is the only inevitability, and the note that creates our new world, or the note whose absence makes evolution impossible, can we really afford to entertain its detractors?

I second that….thank you!

Thank you!