The So-Called Negro's So-Called Jazz

Malcolm X and Charles Mingus said it would be alright if we changed our names.

Malcolm X and Charles Mingus shared the endearing syntactic habit of placing the phrase “so-called” in front of words that tried to define them or their work with connotations they disputed. Shades of meaning are often more potent than the most obvious signifying, hence the tradition of ‘throwing shade,’ or ‘shade as a form of reading,’ and they were throwing the shade back. For Malcolm it was the so-called negro and for Mingus it was so-called jazz. Neither man was nitpicking for controversy or scandal’s sake, on the contrary they found an efficient and subtle way to question inherited language and ideas in conversation, and let it become a reflex.

It takes a change in the collective cadence to displace a popular word’s resounding authority over perception, and Malcolm and Mingus both understood this— the spell of patterns and names and how we must break its hold with counterspells and encrypted rhythms. Their shade was retaliation and helped upend and trouble the language the way it invaded and demonized or tried to diminish them; they made it a suspect in the crime of misidentification. Displace the negro and jazz, so-called, so-called, and confuse what you are calling with what comes. Make the negro and his music fugitives or non-entities who must be reintroduced by the their true names or you might lose them forever to your ignorance of who they are. That’s what the incessantly repeated and quipped so-called establishes, a path to our disappearance and reappearance as ourselves.

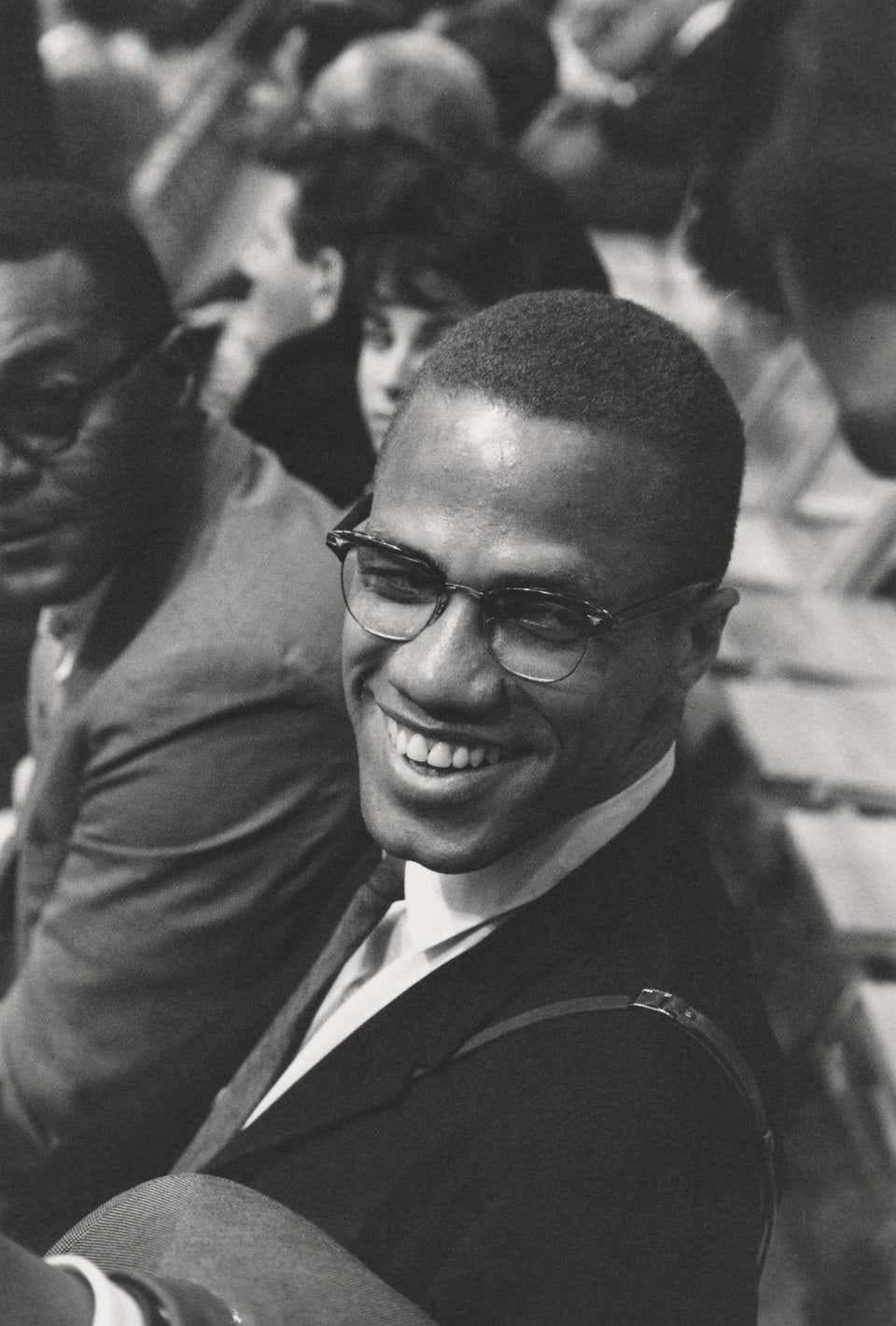

Malcolm’s so-called was quick, barreling, rapid fire, the kind of glancing tone that sticks to you as if it’s a visual glare. He was a master of hurling effortless linguistic darts with a smile too beautiful to fault. It’s painful to witness how sensitive he really was behind it all. There’s an ever-present glint of sorrow in his eyes as he deftly wards off yet another belittling comment from some news anchor using his suave, above-it rhetorical combat. Malcolm knew that negro was shorthand for death, necro, crow black— not just dark but dead, and his deliberate rejection of the term, even mocking of it, was what helped to wake us from the trance of its polite usage.

Names matter, what you call a thing, that thing becomes, even if only for you. The negro and the so-called negro are dead like god is dead. Who is the negro? Or as Jimmy Baldwin says... it isn’t me. The negro is dead but the nigga lives. 'Nigga is infectious, fun to speak aloud, a sometimes glamorous, guttural calling of appreciation and love or playful contempt among black people— a taboo moment of silence for everyone else. While negro sounds broken, disjointed, like a man buckling under the weight of his shamed image, nigga is proud and self-assured, re-appropriated, the negus, king among the dead. The nigga lives but the so-called negro is a corpse in the language. Malcolm lives but the so-called negro, angel of death in the west, we don’t know him.

Mingus’s so-called was rumbling, searching, a little agonized, a little disturbed but overall very matter-of-fact. He spouted the qualifier during every interview, drummed it, blurted it, smiled it out, growled it out, depending on whether he was speaking to a friend or some kind of student masquerading as inquisitor. He knew that jazz was shorthand for jizz, for libinally charged sex music coming from the whore houses that eventually made it to the radio and into popular graces, against the wishes of the pious. He once joked, at one point I thought maybe it would be safer to be a pimp than to be a jazz musician. What he meant was, everyone assumed he was a pimp anyways just because he played so-called jazz music. The level of study and devotion that it took to become a musician and a composer of his caliber was overlooked by most lay listeners. Everyone was preoccupied with what listening to or playing jazz meant about the way you lived, and underneath that, the way you fucked or wanted to be fucked. Black music was reduced to the phallus, to arousal and lust and quick fixes and its depth and seriousness repudiated. Mingus’s so-called reduced that reputation to rumor, denied affiliation with popular concepts of black sound, and let him carry on with the business of creating music that was willfully beyond category.

Part of Malcolm X’s message was that it was better to have no name than a false one. For him every black person with a name handed down by a slave master was a so-called someone, allegedly who they said they were, but in his words still a slave. The beauty of not knowing your true name is that you exist in part as a myth, no one can speak anything shady over your life because they can never quite locate you in language. On the hand, no one can speak great honor over your life because they can never quite locate you in language. The X is like a new, self-instantiated location reinstating autonomy and making you available for honor and glory. Mingus comes in and says if you call yourself or your music (your sound) by the wrong name, nothing comes. Names under capitalism are often brands, rituals of opportunistic calling ironed into the skin by consumers and marketing teams, the new owners and overseers. To take off a name is like shedding a coiled, long-held scar. At first you feel for where it was and almost miss it, but eventually you behave as if it never existed and memory of its obstruction is blurry and jarring. I think we all have some fear of losing scars, names, real or imposed, and tones, true or contrived— the kind of fear that is really deflected hope. We all resent the theft of potential that is calling something or ourselves by the wrong name or title, so pretend we never have and turn identity into a series of losses and missing pieces we spend our lives trying to integrate. We pretend who don’t behave exactly as the names and titles we allow into our lives and psyches dictate.

Sun Ra chimes in with lines from a poem of his: death speaks to negro: you are my servants, you are my servants in my name. Nina Simone joins I told jesus it would be alright if he changed my name. If Malcolm and Mingus didn’t offer incentive enough to give jazz and the negro away like haunted belongings while holding onto ourselves and our music, Sun Ra makes it irresistible and Nina Simone makes it holy. Think of Prince from this perspective, changing his name to escape a predatory recording contract, but branding himself with slave written across his cheek like a network of X’s, as he left his government name to them— it would be alright. Think of how many rappers whose government names you’ve never heard and how calling them would change the whole vibration of their music, hold them captive outside of its sound. Mechanized terminology is exhausting these days. Meaningful words and names are being made into clowns and jesters one by one until all we’ll have left is speechlessness, negroes, and jazz. A moment of silence for the so-called revolution that might come once we stop calling it by its slave name. A moment of reverence for Malcolm X and Charles Mingus, two men born under the sign of taurus, great orators by nature, who understood that the so-called truth was just a well-guarded rumor at the heart of black music, begging us to give it no name.