The Afro-Horn Was the Newest Axe to Cut the Deadwood of the World.

Liner Notes for Henry Dumas's "Will the Circle be Unbroken."

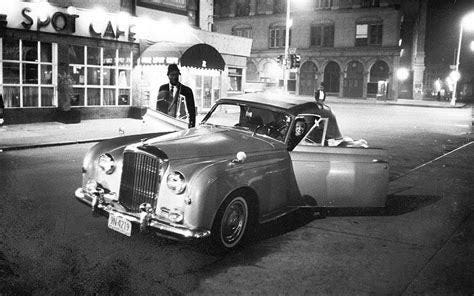

A loop of black sound combs and shields the aura with blues cadence at the entrance, near the stage, at the neon leave out place. The club has been many things for black people, once we escape the instrument of terror that it risks becoming when circled by police or the wrong kind of spectators, we get a territory all our own, a fantasy/sanctuary/open secret that is both commercial and not for sale. It took a while to get from the minstrel show, sideshow, medicine show, fugitive running away to the stage trope, to Congo Square on Sundays, and the Small Black Church, the Woodshed, the cypher—but when we got there that unleashed spiraling became a ritual of return, a way to get home without leaving captivity, and threats to our self-actualized performance practices and spaces became subtle war cries to our senses. This was arrival in the arrowed shield of our hope for ourselves, our ability to hear and witness ourselves without the chatter of oppressive gazes competing with our looking or othering our practices, dissecting them like anthropologists. The black-owned and run club, as rare as it was and still is, guaranteed creative and social freedoms that nowhere else did at its inception. Labor and despair on the outside are replaced by the ecstatic groove of refuge and the music becomes the only law we need, root of all our natural and self-soothing obedience.

Henry Dumas’ “Will the Circle be Unbroken,” is a story as ritual about the will of black sound in impossibly free spaces, and the music’s magical content therein, which retaliates against anyone who would dismiss it to attempt to enter it from the outside with the sense of entitlement of a consumer or buyer of a commodity. Three white hipster jazz fans, the critic/ part-time musician/ full time know-it-all types, try to attend a private, blacks-only jam session at a Harlem club, underground famous for its ‘afro-horn’ and ‘Probe’ the horn player who has mastered that rare instrument. This club is also known for its exclusion of white patrons, who are told not to attend for their own safety. The trio of white hipster intelligentsia however, feeling invincible, feeling like Mailer’s White Negros, name drops Probe as an acquaintance at the door, and when still denied, calls on a stern white police officer to ensure their entrance. Their wish is granted, they get inside, they listen, they die. The music pulses through them like an energy weapon or a wound, a frequency their bodies cannot carry or outrun, like their own blood turning on them in a too-bright sun. They had been warned, so that when they are nuked by the horn, their collective surrender is almost instant— flesh slumping and shrugging into a mist of retreat. The session ends like a rope, broken fable of the great black and blue hope. Probe walks cooly offstage but lingers in the hang of the words like a killer and a healer, both, they way truths we don’t want to face can be both at the same time until we do face them.

The brilliance of this story is that it never ends, it spends a silent eternity sweeping up the bodies in its audience again and again, and that loop, rivaling its own birth to bring it about over and over, feels more like music than words, feels like singing, a hymnal disguised as prose. And what about that phantom club, where can it go from here? A sudden graveyard charging forth as festival, evidence of things not seen. A triumph of rhythm that proves black sound’s justice, and its limits. Venue, space to become in sound, is rarely without its soft ballad of battles to determine what sound, what becoming, who gets to come and where are we going when we enter? Dumas’ revenge fantasy as singing-story dangles at the entrance of any music venue you enter once you encounter it. Would you risk your life to listen? What are the stakes of the music now, do the demographics of live audiences reflect the intended audiences of black music? How do you mend a circle with revenue at its center instead of authentic artistic evolution? The simple equation Dumas offers us, unfolds like a scientific method—make the colonizer regret their desperation for access to your energy, stay cool when the access overwhelms them, walk off stage when it kills, the show is over, the experiment done. The non-performance coerced into publicity and exposure, forced to shine and perform against its will, comes out to show them. This simple and confounding story explains a lot of the tension between what we want to hear (what we desire as sound) and what we’re capable of assimilating without drowning or becoming estranged from ourselves in the intake. Why are we so greedy for tones that would neutralize our own? Why is black music the most hypnotic substance on the planet, untapped ambrosia?

I think of Eric Dolphy’s sound as the one Henry Dumas conjures in his tale, because of the way Dolphy could loop on flute or alto, because he was both haunted and warm, ancient and yet-to-come, and because he disappeared into the magic knot of himself like a mystic when he left this planet, not like a victim. When asked in an interview by a white critic how he came up with what to play in his free, atonal, fire music, Dolphy, audibly a little unimpressed with the line of questioning, replied, you can only play what you can hear. You can only survive the music, the tone, that you can hear. The frequencies you don’t hear exist without you knowing it, prey on your obliviousness to them, and can undermine anyone who would pretend otherwise try and fake that access.

Proximity to black sound is treated like a narcotic here, however, spectators want to be played even the tones they cannot truly differentiate. If patrons have to risk it all to test their range, they’d rather do that than be exiled from the circle they broke into so eagerly, obsessively. There is no better allegory for how it feels to share your music or your sound signature, in ways that defy it, to be loved for the same sounding you’re despised for, to only deploy your weapons involuntarily, when people mistake them a field of dreams or dinner and a “show.” The break in the circle is a result of our need to name its form for these obsessive others who chase it. We break form in naming it, but through that rupture or puncture or invasion are the millions of radios that render the sound infinite and let the song through, past its idea of itself, to its true being. Spectators and critics are always already dead in the eyes of the true black song, only the singer or deliverer survives it by staying inside it, and even inside that song you might snap thinking about the police and vigilantes on the perimeter, and become the scattered limbs of their rhythmless understanding. The circle is broken now like a curse is broken or lent back to its sender, and mended into its intended form with this endless ritual of entrances Henry Dumas gave us before he himself left the club like a sacrifice.

After Dumas was killed by the police outside that never-ending doorway between fact and fiction, his sons both committed suicide. The circle is still alive like a serpent, and Probe is its eternal head, resting backstage with his afro-horn, ready to avenge the ones who violated it.

Reading this felt like a firm embrace.