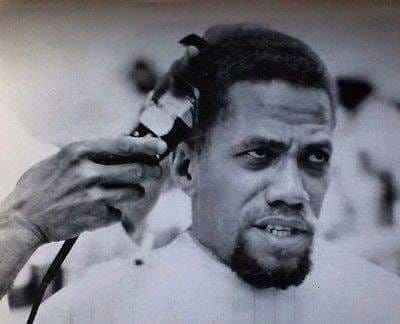

And my heart is torn between being cruel and being kind, and I see the same doubt in a cat’s eyes. And I see the same burden of ambivalence in Malcolm’s eyes as they meet his image in the barbershop mirror—unsentimental horror and an agonized self-approval revealed by his refusal to undo the contortions of exhaustion that mark his face and shift it to grimace or a silent howl for mercy. He taunts himself into an eternal present and dares himself to recoil from its toll on his heartbreaking beauty. He prowls softly in the limbo between groomed and free. He needs a haircut and human touch that asks for nothing in return and seeks no affirmation from him. The mundane tenderness of tending to one another in trade is here. A hand, sinewy and a little exhausted itself but clearly intent and steady, holds an electric razor blade just behind his hairline, cropping it into obedience. No amount of haggard stray hairs or knotted knuckles detracts from the choreographed perfection of this scene, the doubled tucking of hand and gaze into an invisible barricade where it’s safe for the revolutionary to indulge some private vanity and be a mere man, to see himself, his image, no longer belonging to him alone, caressed by sharp inflections that prepare him to give himself away again at podiums, make him worthy of the beady-eyed counter-gazes always stalking his movements. His eyes meet the mirror as if everything is suspicious, especially the stranger he calls a self, jaded by toil into the prone position of speechless recognition before a smile or a scream.

In another shot, taken moments before or after, with the hand and razor identically positioned, Malcolm wears an infinite grin as if the razor’s motor is a music rousing him from inner turmoil, giving him some agency he had forgotten about or neglected beneath the dehumanizing duties of what is reductively called public life. Is it simply “public” if the so-called public feels as if it owns you and governs all interpretations of your character? Are death threats, fire bombings of your home, obsessive demands for rescue, and turmoil at every level of interaction the commonplace wages of having a public? He is the constant prey of vultures and fanatics. These photographs disarm us and Malcolm, because they are as close to candid and off-duty as any we’ve seen. The grit that they possess is the humility of spirit and sense of humor inherent in Malcolm, he’s facing the slight disarray of his appearance with candor and ease, welcoming his fray, and celebrating each small upgrade with more gratitude than impatience to be relieved of the disheveled look. What’s the ambiance? What is on the barbershop radio? What is whispered in the ear in the razor’s intervals between buzzing and gauging where to travel next on the head? Is there a federal agent or spy somewhere in the room; was the FBI keen enough to realize that the intimacy of black life is often tied to our hair and our grooming, black therapy is the beauty shop or barber shop, the real head shop.

I imagine Eric Dolphy’s tone emanating from corner speakers pitched down into the room above a wall of mirrors. Dolphy’s tone blends intensity and expansiveness and always chooses to expand instead of alienate by plunging deeper into seriousness, he refuses to get so technical that he loses people and becomes more cerebral than real. Malcolm is similar. In the film that I invent in my mind that includes this scene in the barbershop, one of Dolphy’s rippling loops on his version of “God Bless the Child '' spars with Malcolm’s laughter and the clap of the electric shears. Maybe I make this quick association because of the spiral or bump that lived on Dolphy’s forehead like nature’s antenna; it’s a sign of absolute receiving for a third eye to make its presence known on the face and not detract from the face’s beauty. In the smiling snapshot of Malcolm in this shop scene, he too has some kind of tangle of skin on his forehead, a slight bulge that does not distract and is only visible if you’re scrutinizing. We communicate in scars and marks and somatic gesturing as much as in words. That feeling of having a birthmark in the same place as a friend or a lover knowing where your hidden birthmarks are, we covet it playfully because it feels like destiny and closeness, a chosen biological kiss or bond, notions kissing, and insinuations, not only lips, and absent of lust.

Malcolm X and Eric Dophy share the dignity of a creative ability and intellect so intricate that it has to smudge a little to translate itself to popular forms and embrace a public. Choosing to allow the mass of erratic attention instead of becoming reclusive or elitist in the face of those gifts is a conscious, open-hearted decision and the disposition usually matches that. I cannot find an attribution for the photos of Malcolm with a razor to his skull, but I imagine maybe the year is 1964, the year Dolphy died after going into a diabetic coma that attending physicians in Berlin called an overdose because of stereotypes surrounding jazz musicians and substance abuse. Dolphy did not even drink alcohol, much less indulge in narcotics. He had collapsed on stage and entered the coma while trying to perform a concert. He was thirty six. Less than a year later Malcolm X would collapse at the Audubon Ballroom after being shot down in the middle of delivering a speech and he would die at thirty nine.

I don’t know if Malcolm and Eric Dolphy ever met in person but their souls were on the planet at the same time for a clear reason, and the rare melange of confidence, a modesty that could be mistaken for timidity, and a singular bracing tone to both the aura and the voice unites them across distances and destinies like matching birthmarks. Maybe after Dolphy pierced through the speakers, a more popular sound of the era interrupts the wry blues riddles of them that’s got shall get with bursting hooks that anyone can sing along to, perhaps James Brown’s “Maybe the Last Time,” also originally released in 1964, and foreshadowing the narrowing of days and duties for Malcolm. You wanna give your heart a little ease… Brown croons… it may be the last time—I gotta scream, he warns.

The other incident when Malcolm’s visage transitions from a worried and tense furrow, to otherworldly serenity in back-to-back photographs, is his assassination. This day would have been just another powerful speech in Harlem in the winter of 1965, but when he was killed while speaking and brought out on a stretcher in front of astonished crowds, wounds and blood covering his flesh, the look on his face then is one of total unequivocal relief, and an ambrosia of calm approaching bliss. It may be the last time he had to scream. My first thought when I saw the barbershop photos was concern that any hand that close to Malcolm’s head was predatory. My first observation when seeing the assassination footage and photos was how ready his face appeared, how transcendent. Are there many cases when presence for one’s mundane expectations is more strenuous than leaving it all behind? The public and even the official record may get the motives of those in this position wrong, confusing militancy with bitterness or sophistication with arrogance when in fact militant and devoted men and women are afflicted with endless optimism, what we rage for is beauty, what we demonize is pain and ugly-spirited types who wait out the revolutionary sound in favor of party music, or are so afraid to fall on stage or in public that they never quite perform, never find a single courageous act.