I was whistling all of his music and then I found out he was dead. — Amiri Baraka on John Coltrane

Everyone is born into a rumor, her own, that she may arrive one day, on time, through a lane of light called a mother, into matter, and give the idea of herself a name and a home on earth. The name, her rumor manifest, confirmed by a form: the body, with its rooms full of evidence that the name is true. Within that form so many personalities can arise under one title, often misguided and short-circuited by spoken language, that meta-tones and grunts and cinched screams and squints and wiggles, writhes, whistles, mumbles— all try to compensate for what words miss when they attempt to call us forth, or what remains unborn without textures that exceed words.

The space between words and thoughts is thus swarmed with relevance and becomes our music.

Sometimes that space begins building momentum in grunts, sighs, giggles, moans, cries, and whistles, the vocalized noises on the the margins of words. There was a rumor that a young boy of fourteen whistled outside of a grocery store in 1955, they called it a “wolf-whistle.” It was said to have been directed at a white woman and for that soft, shrill alleged sounding he was killed and swarmed with relevance and his name was Emmett Till. We’ve scrutinized the scenario over and over as a culture, stolen its drama and use it to prop up other incidents, stolen his mother, Mamie from her wails and will to power. We act as if her choice to keep her son’s casket open and expose the horror his killers inflicted was a collective decision, we appropriate her courage. It was only hers, voyeurs have no valor. Her son lives forever because of her choice to let his whistle scream.

What superfluous love and mischief lurks in a sudden whistle? What calling into being of what playfulness and what hysteria travels on the thin wavering line between gasp and gust we call whistling, a form of telling ourselves secrets in public, a polite diversion from the blankness of it all. What was terrible about Emmett Till’s casual hunger for the sound of air on sky-flesh in private celebration? And if it was loud, what is so terrible or deviant about black loudness that it found him dead under its sluggish August river. Why are we offended by the noises that keep us alive and awake to one another? Why not let lips pressed together lightly and spiraling the air into witness be friendly? What malice is there in absent-minded desire? Why not objectify one another on a whim and improvise high-pitched windows into the atmosphere to say hello. We never greet one another anymore unless caught by surprise or to hide behind pleasantries. What’s so bad about the dandy or the dreamer that he has to die singing and then gasping over a remark as reflexive as skipping or giving a friend an exclusive handshake? Why do we feel entitled to the hyper-reverent silence of monasteries as we pass the living on sidewalks, in cities, full of synaptic impossibilities that only noise can heal or render as ease instead of shame? Why are we ashamed of our sounds or any sound (hear also suns, the bright light we orbit around and create with our bodies) no matter how quiet or intense. What is criminal about a sound? Why is this shy adolescent serenading a scar on the landscape of wonder, a tragedy that mesmerizes us and spits us back into its rotting belly to parse its endless sound as images, forever? Why are we afraid to whistle now, somewhere where we need to to call one another, stifled and folded into idiotic hurdles because the whistle-song is lethal.

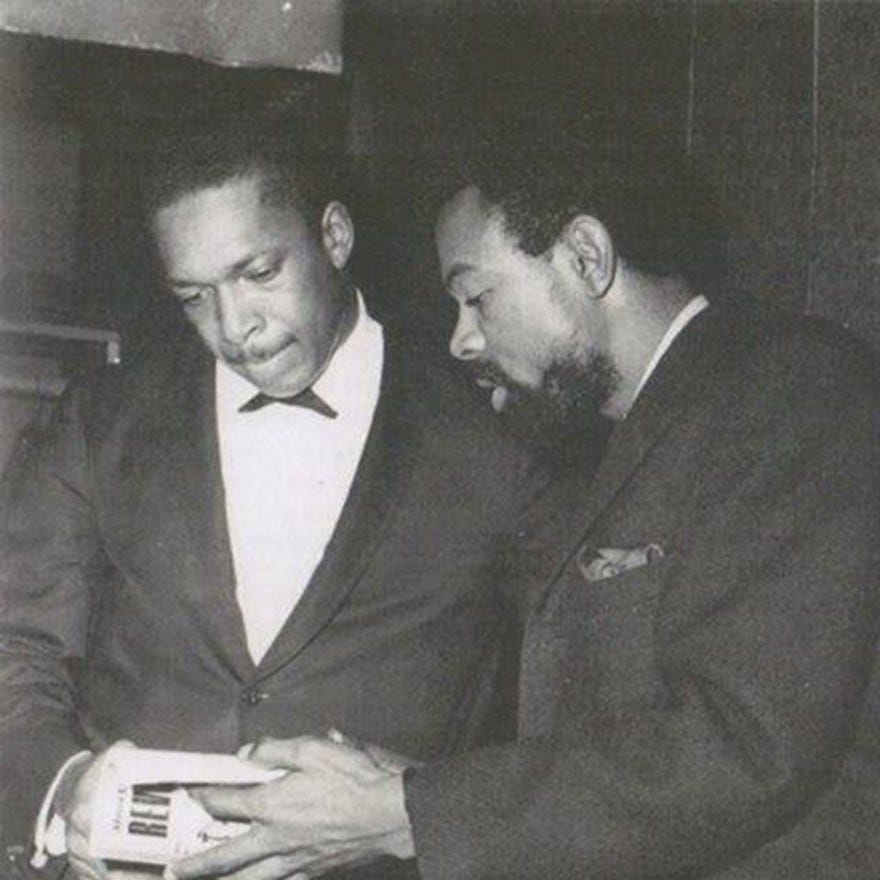

Here comes the whistle man, cries Rahsaan Roland Kirk, in one composition, through harmonica and kazoo and a zoo her traipses through whistling to himself as he passes a pride of caged lions and survives his secret wonder, a lucky one. Whistling is a way of cleansing the listless or lustful silence with exuberance, it is justice returning in a loop, a form of clapping with the mouth, a light applause for what cannot be called by name, and a demand that something come back, either in echo or composure. Amiri Baraka was in jail after the 1967 Newark Riots, a very hot July in solitary confinement, and to soothe himself he whistled John Coltrane melodies A Love Supreme, A Love Supreme, wouldn’t you? A guard came in whistling off nothing/accompaniments and slipped a newspaper clipping under the cell door. Coltrane’s obituary. He had died while Amiri was locked away with a bulge and bandage on his head rehearsing his solos for slow air. I was whistling all of his music and then I found out he was dead, Amiri put it.

Is the whistle a tunneling psychic invitation into a subconscious world attached to this one by whatever lets us fear the things we desire most— casual freedom to be music and leave words looking for us in their sounds instead of the other way around. Is the whistle a moment of forgetting our troubles and living in the now for which we risk amplifying the trouble? Is it clumsy to sound as satisfied as a whistle does, like Otis Redding does at the end of “Sitting on the Dock of the Bay,” with nothing to do but sound like himself as he wastes away. All day, every day, nowadays, electronic devices make petit noises that we ask them to make— our sweet leashes telling us when to go and where, how to navigate our digital twin’s footprints, and no one is punished for polluting their environment with these sonic ticks of chaos. So why when these noises come from human beings and are softer and more directed and tangible and mean more because we had to breathe our life-force into them, are we so repulsed and inconvenienced, suspicious. How long have we treated natural noise like a crime and manufactured machine acoustics to override it? Why not go outside and mimic the machines that are copying us. The bait wants you to desire her, but if you express it as happiness and not torture, if you whistle instead of yelp in the agony of longing, or if you don’t make any noise at all, she’ll accuse you of criminal indifference, invent a squeal, or pass you your hero’s obituary and look glad to deliver the news.

The deepest whistle is extended to the whistleblower, the final hero before tyranny— how is she informed and inspired by the earliest martyrs to whistling, by Emmett Till and Mamie Till and Rahsaan and ‘Trane and so on? How can we be sure that more people spontaneously speak the truth and survive it? If whistling is so abrasive, should we use popular music to expose and uproot tyrants instead, do we already do this in code, is the code-switch like a whistle alerting us what beat to carry as we go forth and tell no one about the revolution no one will do but through sounds no one will believe until they move with them, whistle them, risk turning them into legends and jingles to turn them at all? Finally the whistle is like spinning so smoothly you are your own edge and the whistleblower a restless god of brinks and edges. Arrest this man he talks in maths, he buzzes like a fridge, he’s like a detuned radio. But then what? The whistletone is endless and will not be withheld.

I just read this and am breathless. I once told a big kid to stop whistling in a locker room and apologized 40 years later. Why was his world turned inside out alarming to me? I was broken-hearted after the death of my brother and his seeming happiness was an intrusion on my brooding, I suppose. Maybe his brother had died too. I don’t know. I hum and hum and hum now, and whistle back at machines that beep and tweet at me, mimicking what’s outside not in. I’ve hummed A Love Supreme quietly a thousand times. Coltrane whistles full-throated throughout time. Emmett Till, too, whistles throughout time. Thank you for this awareness, Harmony Holiday, and for once again singing the truth. All this is to say, read this poem by Etheridge Knight, the last line is the answer to why: https://allpoetry.com/As-You-Leave-Me