Would my spirit grow exceedingly chivalrous, instead of succumbing to a daintiness that would match my petite frame—sure. Maybe I’d inherited some of my dad’s mystical chauvinism. But I’d emerge tender and discerning, and sweet beyond the intellect. I suppose from the outside I could have been called a wounded child. From the interior I felt all-powerful and unimpressed by most assessments of most things. I felt as if I was channeling a series of secret frontiers. From that impossible vantage, I would have to establish my own rubric of values. The chivalry was the result of a biological urge to avenge the forces that took my father, an urge that demands my heart expansive and roving like a searchlight still touring the premises of the crime scene for suspects. I entered a who-done-it kinda life where all the aimless blame really refracts onto me and my penance becomes this unrelenting lyricism, always inching toward liberation through griot mysticism.

When J Dilla died in 2006 I was a student at Berkeley, so crossed the Bay Bridge into San Francisco to attend a show memorializing him. Part of me was attending to claim what’s mine, to reinstate my relationship to black music after a long hiatus where I had tried to be a civilian and circumvent affinities that scared me. Dilla’s death taught us that we had to learn to cherish innovators, and to define our music while it was alive, not only after decades of awaiting the approval and sanction of white critics and admirers. His leaving was the closest our generation knew to a leader being taken out by the state. It felt like theft or a yanking back of cultural bounty. And it mobilized shocked fans, who took to clubs with banners and chanting J Dilla changed my life, the club mantra of the decade. My mother, critic and admirer, had been dating a drummer named Derf Recklaw who had traveled to Brazil with Dilla to make a documentary, and so I was on the list that night. Something shifted in me in the silvery darkness of the Mezzanine as it lurched and stilled with grief and awe. I wouldn’t be able to tiptoe around the perimeter of my destiny much longer if I wanted to remain eligible for it. I’d have to participate, and not just by listening and consuming music, which without other modes of participation feels almost parasitic. I’m not a spectator, I’d have to act. If I was going to be in it I would have to be backstage, to see its guts. Watching from the outside felt like coaxing myself into the blur of a lie and it made me restless. If my childhood had taught me anything it was that the view from the audience is false. James Brown could dazzle any stranger, and then show up on the news the next night for punching his own wife. High on cocaine he’d shout Living in America as his alibi, and we’d all be charmed enough to forget what he might have done to a woman with no face.

The important thing is to not become that woman, I’d always thought. But then one day the important thing was to become that woman and prove you could train the man out of becoming himself. Circus instincts. Minstrel and Medicine Show antics. But from the audience, I couldn’t even trust what felt like a patch of pure solidarity around James Yancey (Dilla), because what if he had been secretly evil or destroyed by someone else who was. I was watching puppets on strings and the strings were frayed and wilting cotton reminders— you could see the hands of industry in their sulking mouths, and the drab scandals passed off for glamor were so boring unless you were part of them, in which case they were boring still but at least you could be sure. Last time it was easy to deceive my heart. Betty Carter admits and we agree. This time not taking no chances, she promises, and we mishear this as permission to engage in a game of chance and chase.

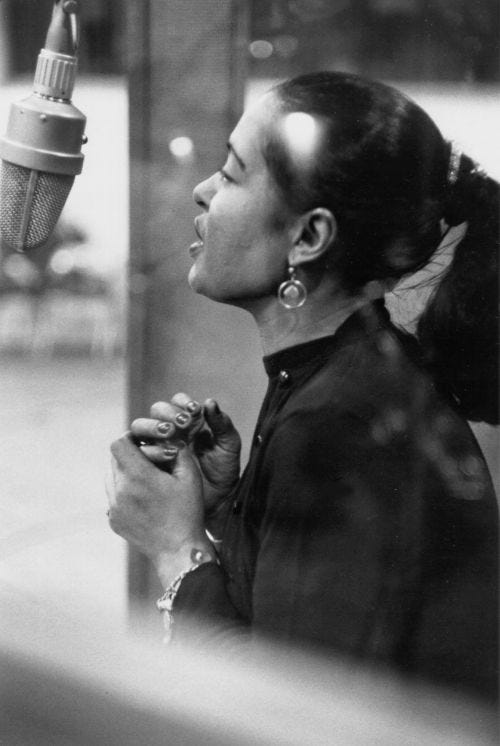

Miss Holiday as Miss Brown is my perfect comeback anthem. I’d come backstage with them, two halves of one woman. Who do you think is coming to town/just wait and you’ll see, Billie lilts in her infinitely recurring rasp, chipper with her burdens. She loved singing this song, and gave it the momentum of a blushing group of teenagers on their way to their first important party. It’s a frightening song because it never recovers any disappointment, just a sparkly optimism all the way through. From the outside that’s the heartbreaking part, we know Miss Brown is doomed to become a Mrs. We know her innocence might be snatched and the easy-going melody is just too smooth to last. Cue Abbey Lincoln’s hymnal She Was as Tender as Rose, in which a girl goes to a party naive and nubile and comes back jaded and ravishing with over-compensation for her newfound heartbreak.

We’re told Miss Brown has sharp eyes though, which is promising. She might have sharp enough instincts to outwit the devil-may-care in herself and her suitors. Who do you think is going backstage, just wait and you’ll see. I can chide myself now for the childish but very real entitlement phase my spirit entered upon the death of J Dilla. That mood, which part of me is still in because it’s me and it’s mine, allowed me to revisit my own father’s death and also to look closer at the hip hop producer’s reliance on the music of men like my father to get in or get on. The splicing, distorting, abridging, and upgrading of soul and jazz music enacted through sampling gave me a double permission to resent and embrace this craft built on desperate disaffected and deeply sentimental safekeeping, a neverending improvision with the past. The voices of the men and women who showed up in the shadows between beats in Dilla’s sound, were versions of my father being rewritten into a present they both never asked for yet insisted upon. My own genetic code was thus rewritten or reinstated in new cadences, turned inside/out and given a chance to re-evaluate itself and edit the sad parts or relive them. Prince had an enduring disdain for excessive sampling, maybe because he understood what it feels like to be haunted and didn’t think music needed more phantoms, or maybe because he understood what it felt like to be stolen, stolen from, and forced to resort to theft to steal oneself back. Hold my phantoms.

The best black music happens in secret. Here our fathers could visit disguised as back up singers for downcast party grooves. Our secrets could visit our hip new territory and raid it for traction. Was I on the list like a mark? I moved to New York the next summer, taught dance for Ailey, began graduate school, and a love affair with one of Dilla’s closest collaborators, another producer, who had been chopping up the bones of my father’s songing until he landed on me.

In 1956 the rumour circulated that Lady was going to appear at the Flamingo in London. In those days it was situated in the basement of the Mapleton Restaurant, Leicester Square and opened on Sunday nights at 7.00pm. The ridiculous union ban which prevented us seeing all the great American stars was on at the time and Lady wouldn't sing without her piano player, Carl Drinkard, so there was some doubt whether the rumour was kosher. I stood outside from 6.00pm and was first through the door and I laid siege to the spot right in front of the microphone (only one in those days). After about an hour of a little quartet playing the mc announced that a famous American piano player, Carl Drinkard, was going to entertain us and the place buzzed -- Lady would sing. I was close enough to her to touch her but wouldn't have dared, she was a goddess and she sang like an angel. My circle was complete; I saw Pres with the JATP in the Lord Mayor of London's Flood Relief Concert at the Gaumont State Theatre in Kilburn, in 1953 and now I had seen his twin, Billie Holiday. Forever, I knew that I could die in peace.

This is everything…