When my dad shot his middle finger off while cleaning one of his guns, the first thing he did was run over to the piano to see if he could still play. After the relief that he could make do without that digit, came the concerns about loss of blood and mending, afterthoughts. In a world where music comes first and is always urgent and beckoning, it is important to become music, to mimic song until your very person sings, to be dad’s piano and not his gun flung middle finger cursing the air as it swings.

My favorite songs of his are the ones that feel like our living room in Iowa during my earliest years, like memories of him rehearsing or doodling at home formalized by the act of recording. A part of me has always needed subtle ways to flaunt the difficult magic of domestic living with someone who spent his life on stages, to argue for the glamor of that quietness and also to take pieces of myself and my family back from the public story. No one wants to be swept away in the gravitas of fame adjacency without her own rituals of witnessing.

At home dad sang and recorded a never-released song called “Midnight Girl” that has been an audial obsession of mine since I discovered the recording on a set of 8-track tapes my mom kept in a shoebox until we digitized them when I was in college and had started asking more questions about the hidden sides of my father. I was learning what questions to ask and what was implicit in silence as I learned more about life and music. Where were the “masters,” a savvy inquisition I finally asked my mother, and where were the private recordings they stayed up all hours of the night making together during those Iowa years. I was told not to make a sound while they tested melodies and tones so I learned to listen and write early, the thick kid-sized pencils were not too loud as they whispered across brown parchment, my plastic toys that mimicked household items in miniature were off limits, I never really cared much for dolls. I took copious pretend notes, unintelligible to anyone but the angels, but the illusion of telling a story in silence helped me pass the time. Somewhere between their muse and their audience I found my ritual attentiveness, never singing along, never even too interested in what they were busy doing, my work was just witnessing, taking it all in while at the same drifting off into disinterested reverie.

When we opened the vaults all those years later, every recording was familiar but foreign, kind of like opening a wound, kind of like stitching one up after letting it mangle in the open air for years. Not closure, but extension of a story foreclosed too soon in the imagination. There were hundreds of recordings, some my mom and dad singing together, some of just my dad soloing and playing piano to accompany himself. “Midnight Girl” was one of those solos, an ode to a love not lost but surrendered. A song about understanding that you cannot possess someone you love, that sometimes love’s real work is leaving or stepping away for a long while to let the loved person unfold as who they are. And sometimes who that person is does not include you. He begins humming slowly as if about to go into a spiritual, and in a way he does enter a version of the gospel. I want you for myself alone, but you’re a midnight girl, he begins that no one could ever own, ‘cause you belong to the world. It crescendos into ballading lament about that surrender, scratches and slurs with the magnetic tape’s dents or dust, but always returns to the scaffolding of his 8 bars of private humming of the sorrow he kept to himself. The sound, because it’s my father, is so familiar I want to rest my ear on its belly as it rises and falls with the lyrics. It’s like going home whenever I listen to it and I listen with a mixture of relief and trepidation because going all the way home is complicated and eviscerating sometimes. The song travels in the same circle it demands of me, it ends with more hums and mumbles after two short verses. I … I love you, but you belong to the world. And then my favorite gesture in many of his songs, he ad libs a muffled yell, a crypt phrase— hurt me but I gotta tell you.

When I first heard this song, my father long dead but never gone for me, I knew it was for me. It was too eerily relevant to almost every experience I’d known socially, and I realized they all began with this idea in the back of my heart that my father died like some kind of black christ, sacrificed himself to save me from the difficulty of living with and through him. I know he didn’t do this literally, he literally broke his own heart in a sense with his own self-regard, his own difficult but sincere love which he understood for what it was. But he also excused himself before he could damage me with it. When a friend asked once about the circumstances around his death I blurted it ‘it was a good age to lose a father,’ as if we shared a similar peacekeeping with that destiny between worlds. I consider “Midnight Girl” a cousin of another one of my favorite songs “I Loves You Porgy,” for its tender way of saying a preemptive devotion-driven goodbye. I love that my dad said goodbye to me in this eternal albeit haunting, ever soothing manner, I love the mythology he gave me.

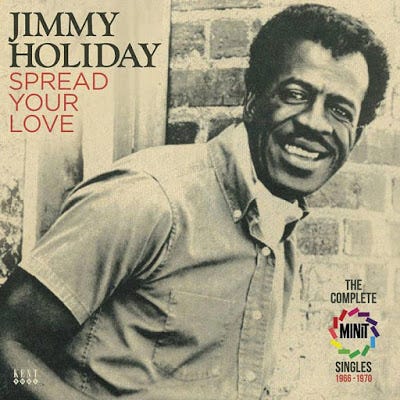

On the other side of his persona in “Midnight Girl” there’s his song “Would You Like to Love Me,” where you hear his weariness, his heartache, where he’s not trying to be strong but instead making a concerted effort to be vulnerable. The lyrics here are pretty self-evident, they ask this question over and over in thoughtful and poetic ways. He compares himself to farmers and flowers, and a chorus of female back-up singers echoes the hook sweetly, would you like to love me. It’s a prayer and chant full of his signature mixture of optimism and resignation. By the end he manages to become the desired object and not the one doing the yearning— the back-up singers ask him in a cutesy stutter would you like…would you like to love me, and he affirms with alacrity I would like to love you, I need to love you, a beautiful, subtle lesson in reciprocity. Also a window into my father’s trickster god side that always lived alongside his bottomless tenderness. Some days I feel situated with him between these two songs, foils of one another, in a liminal space we explore together in our eternal, hereditary passion and ambivalence, vacillating between ‘let me be’ and ‘be mine.’ Other days I turn away from all that flowery essentialism and really am the Midnight Girl, the archetype my father promised me.

The way you articulated the timing & imagined reasoning & implications of your fathers death is hauntingly familiar. I feel like that thought is so deeply intimate, that I didn't realize it was a fully formed thought that I once had until I read it here in this piece. I love that the idea of death as bodily sacrifice. Such a vulnerable and personal way to reconcile.

That aside, your words pay a beautiful homage to the sounds your father created.