It Must Be the Devil

On Amiri Baraka's "Dope" and the poetics of the underdog who gets close to God

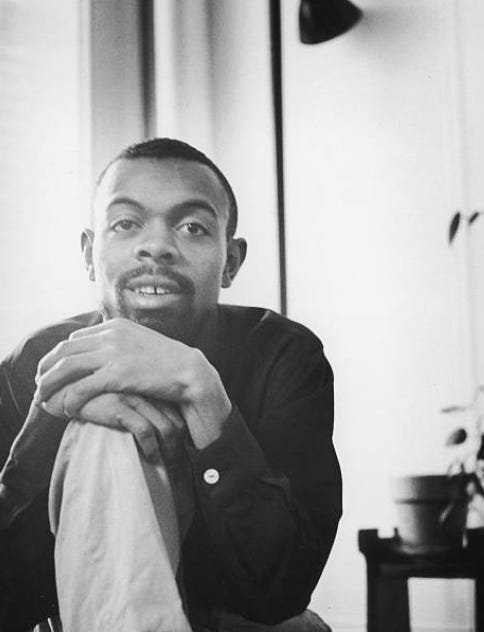

Cherishing the belligerence of underdogs I sometimes forget what it costs them, so busy loving them I forget to ask if they were allowed to love themselves with no disclaimers. It’s melodramatic to wonder if your heroes felt discarded and alone, but inevitable if you really know them, and love them. I’d never regarded Amiri as part of the triumphant underdog archetype until I developed a haunted fascination with his recitations of his poem “Dope” across decades and spanning his every ideological stance and its dissipation or resurgence. The poem is a love letter to the foolish fools who get trapped in pretty lies about empire or ascendency into the middle class as reprieve for all suffering—it’s a love note to all of us that is always about to turn into a death note if we don’t learn now to say it back. It uses dialect against itself to reach the sophistication of prelinguistic yearning, and unless you’ve heard Amiri read this poem aloud, acapella, you might not understand how the words and phonemes arrayed politely on the page are a scarecrow for impossible music and he himself the straw man you have to pass on the way to the soul man, who is also him. “Dope” is the poetics of risking it all to do what you love churning into the scatological coherence of overhearing your shadow tell you to go in both directions at once, beyond yourself, beneath yourself. Its approximations of ruin culminate in delirious grandeur.

Listen. It opens with a bestial clipped moaning that floats and ripples its nonsense into pure suspense. It soothes and you hope he’ll just keep hooting like a hunting animal but that pitch grows too aggressive right at the moment you hope it endless, and he banishes the beast for a more cerebral abstraction,

Ray-light morning fire lynch yet/yes the pain in dreams/comes again.

Most people in pain/yesterpain and pain today

The dialect resumes here as if this is a duet between eras, or opposing versions of the self and of reality. There’s the measured analysis and the frantic revving that interrupts it like a tattletale in school who starts shouting right when a criminal is making a clean getaway. The criminalized element here is frigid, hyper-delicate thought. This ensures that the poem never slips into bourgeois nostalgia baiting; the mesmerizing cruelty of the now-seeped future polices its sentimentality. The tattletale starts his verbal jumping up and down and hand waving, but the authority he’s telling on on you to is the same God he’s telling you to be careful not to confuse with some fraudulent mogul or politician:

ohohohohoh/mus be the devil/mus-is/mus-is/mus-is

It can’t be Rockefeller

It can’t be them rich folks

They’s good to us/they’s good ta us/they’s good to us/

I know/the massah told me so

Wow!-wow!-wow!

Vivid paroxysms of speech have the effect of a fugitive scene in a horror movie, the poem is running away from itself, outrunning itself, to tell on itself, its disastrous inclinations to defer joy based on the promises of its thief. Who is joy’s thief? The preacher man wants to know. Maybe Western thought, maybe every banker and poet who upholds it as law, or maybe the self’s personal scripture that accepts the idea of beauty as consolation for its disappearance into false acts of love and labor. There is a dishonorable level of obedience to this society’s laws among its so-called rebels that can only be called out with these slippages into the lawlessness of tongues. This is a poem as cynical and earnest prayer meeting with the self and any apparatus trapped therein masquerading as a soul so the real soul cannot be accessed. In one live recitation he laments:

It was all commercials/

Him her it them/whatever

Transcendental cynicism is the new devotionalism here. Amiri is glib and belligerent simultaneously on “Dope” recordings. He wrote this poem in the mid-to-late 1960s when he was transitioning from the disaffected hipsterism of a token black beat poet, to the unabashed militancy of a black avant-garde revolutionary. He shadowboxes with himself as he does in much of his best work, from “Something In the Way of Things,” to his Elegy for Miles Davis, to his play Dutchman, to “Somebody Blew Up America,” to “Come Back Pharoah” creating a theatrical atmosphere in poems that give their black subjects the monologues Hollywood never will. And like when the bridges of perfect love songs by the Isley Brothers or D’Angelo, plunge into disheveled pleading and testifying that never lets us forget their rootedness in black pentecostalism, so his poems that make him a choir of one heave into gospel rhythms even when they mock the docility of religious faith. They mock this faith with religious fervor, using the dialect of believers, which is so beautiful it drives the poem to unintentionally contest its own disillusionment with heaven. Whatever terror lures such a poem forth is both to blame and to thank. Whatever prayer this is answers itself and the poem closes

Amen.

Amiri himself would hear the Ra on Amen, the shard of an ancient lexicon clipped off and oversimplified to fit into the tight neurotic mouths of those who believe praise is conceptual and not physical or born of the physical act of saying what you say how where and when you say it. So that on the page “Dope” is the corpse and every time he reads it aloud even just in his head, Amiri resurrects the sun he is praying to for enlightenment, or his friend and confident, musician Sun Ra, who he met with in Harlem every day during that transitional period when he made the poem in his own image, yelling, then worshiping tenderness, like he did. Two decades of reading this poem aloud would pass before the word dope, short for dopamine, became slang for something cool or sanctioned. Two more decades would pass before the dopamine addictions took hold en masse in the forms of pornography and social media, which are not that different from one another, both offering arousal that is short term and needs constant replenishing by those same sources. Dopamine addictions would mean that mood-enhancing neurotransmitter that rewards more hard won, long-term goals, serotonin, would be displaced and phased out for many.

It is traumatic, to watch everyone around you willfully join the zombie apocalypse for clout or dopamine, and the poems that reenact this passive revolution, in the tradition of “Dope,” will be the first to expose it. They might not be as effective, we don’t all have access to that many versions of ourselves, but it is the poet’s job to endorse an addiction to beauty that can never be bought out by the ugly shit we have to tell you about and witness and record to prove beauty’s importance again and again. There is no better poem to hear aloud in English than “Dope” as read by Baraka himself. Its heartbeat of ooooohs snitching and attacking the miracle of itself, is the first poetics of the vivisection, wherein the heart survives outside of the body of the poem grunting and wincing, always threatening to jump back in right when your disassociating has gained its own momentum. “Dope” is the confrontation of your potential with your lag, and it aches, and struts like a dandy before falling to its knees. I love underdogs so much that the reader of this poem is my king, a stray heartbroken wolf pretending it wants to hurt you so you steal its teeth. Amiri uses hostility to soften grief and “Dope” becomes a minstrel show where none of the minstrels smile, they are vicious characters exploiting themselves to get high, but too proud to act happy about it. Amen.

Forgive me for not subscribing sooner. After your current interpretation of Dope, it was time! Priceless! I heard Dope as part of text/CD (Call and Response: The Riverside Anthology of the African American Literary Tradition) many moons ago. Your art and genius are intoxicating and movement-making. It got me moving today! Thank you.