To tell everything is a very effective means of keeping secrets —James Baldwin

Both Jimmys were hopeless patriots; that’s Jimmy Baldwin and my father, Jimmy Holiday. I use Baldwin to forgive my dad, for he knew not what he did, and vice versa, but why is it so shameful to openly or defensively love a country in which your parents or grandparents were enslaved or made minstrels? Perhaps because it feels like a solemn Stockholm Syndrome that even very powerful men couldn’t overcome or decry, being victims of it themselves. Lapping around on the devil’s decaying tongue. And if they were afraid and I entrusted my safety to them as a daughter of some kind, would I too have to ingratiate myself to all that threatened me, as a matter of heredity?

James Baldwin was always tag-lining vitriol against racial injustice in his best preacher’s affect, with a merciful almost vicious, … it’s because I love my country that I’m its biggest antagonist, as if the microphones were a knife or gun to his back. In my dad’s case, he was a proto-Ye who might have been running for president by now had he been born into a different generation; he loved God, and everyone, on his best days, with the unshakeable bravado of a self-appointed bodyguard who sometimes ended up attacking everything he was enlisted to protect. He professed his love in songs, some trite, some shatteringly beautiful in their refusal to be trite enough for the radio. One is this rare cut called “I’m Gonna Help Hurry My Brothers home,” which I thought was an anti-war anthem the first time I heard the first two verses, only to realize it’s him positing that he join the war in Vietnam as a soldier, to speed up the conquest for empire, and for his miserably heroic brothers who were sent there involuntarily.

He interrupts his gorgeously earnest signing with a spoken monolog, in his drawl and slurring phrases, he expounds on this rescue mission agenda in exhaustive detail as if writing a pitch direct to the U.S. Army, patriotism as humiliation ritual, as unrequited love. To recover, I have to think of them as undercover secret intelligence, spies, who by pretending to love their country became important and formidable players despite growing up poor and entirely disenfranchised. It’s up to me to scorn or question their martyrdom and our country, hurrying our fathers into the wings where they sing about rebellion and tricking everyone with slick, simple rhetoric, ennobling themselves with gifts of language instead of blood. I find myself wanting to apologize for or mistranslate their decorum to serve my own ego, and our collective reputation, and then I remember their moments of belligerence, my decorum, my internalized shame for any artist who can be pacified by status, even a little, even myself, especially now, especially forever, can we pretend to make music as if we have no country to defend or disarm.

—

Decoherence is the process by which a quantum system loses its quantum properties, and surrenders some of its information to its environment. It is compromise, the subliminal side of civility, wherein one might become the version of himself that most suits his surroundings, rather than forcing the environment to accommodate his favorite form of self-delusion until it concretizes as an almost true self. Before an object de-coheres, it is infinite and possesses the capacity to do or be anything it chooses. It swiftly collapses into the finite, the pathetic-mundane. That diminished version is who and what you encounter in the physical world, a pandering translation of impossibly diverse potentials forcing them to assume a structure and enter language that names said structure and assigns it meaning and use and value.

The best bast black music resists decoherence and is called jazz or improvised, crudely spontaneous, for that refusal to be one thing, and is alienated or domesticated until it conforms to a unified and limited system or genre, at least for the duration of a song. So too with the makers of that music; songs disassemble and reform in the image of a saved, god-fearing version of the singer (see Al Green after the grits, singing exclusively gospel music). This diminution for the sake of the brand, the commodity, the market, the oversimplified and hyper-fixated fanbase, the backers, the political climate, the FCA— is seen as a necessary concession, good sportsmanship, but it’s been so normalized that most art and music is very bad lately, having given most of itself over to the state, the industry, or the narcissistic auto-erotics that occur when an artist pretends neither exists. The work is so predictable or derivative that it signals the empire is truly collapsing and no allegiance from black artists can dissuade it from suicide.

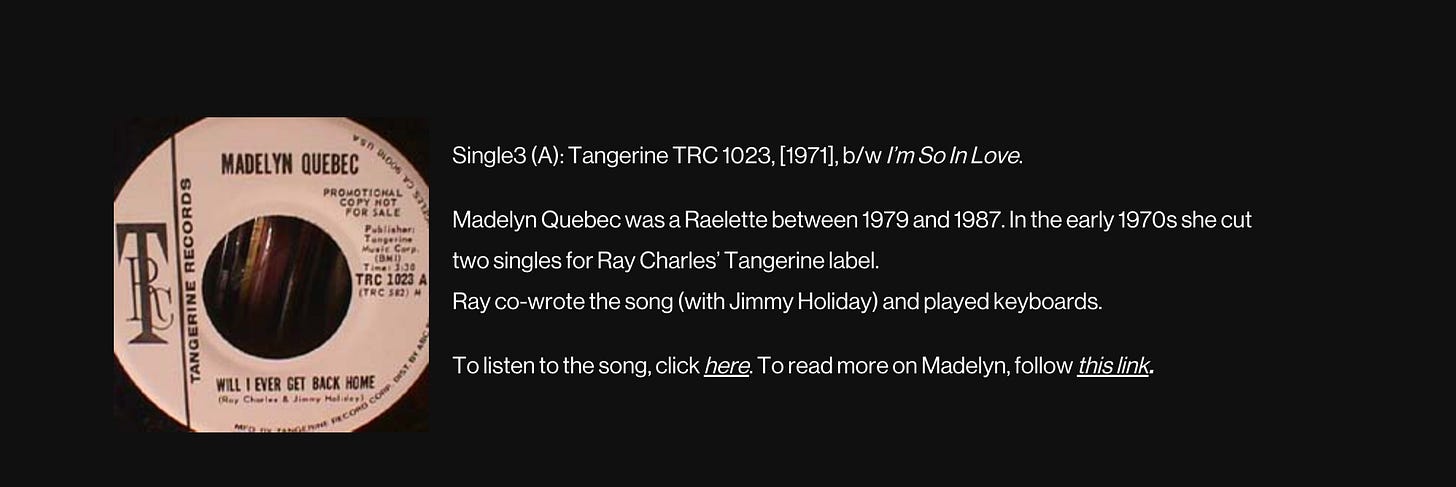

Nonetheless, they try, now needing the gig, and ritualized patriotism in song or literature feeds the beast as decoy so some can go on to be unapologetic rebels defying that meek protocol; theirs is a controlled, deliberate, decoherence, the ballad of the sad young men who know better than to admit why they’re sad and sorry, so act like soldiers and free the gentry to sing along before turning on them to invent a sovereign sound. Having used up the opportunistic respectability themselves, though really meaning it and not intending their volunteered nationalism as mere opportunism, they free us to be banshees and dreamers who scream you don’t know what love is, into the crypt throughout our vanity psalms about pseudo revolution. Then love comes back to me, the chipper way Nina Simone reinstates it with that line in a live version of “I Loves You, Porgy” Intimacy is restored backstage in two miraculously congruent acts. I read Baldwin’s short story “Come Out the Wilderness” for the first time and realize, because what the story offers is an arresting account of a black woman of twenty-six, living the Greenwich Village and working at an insurance company while coddling her white failed-painter boyfriend with all the shame of a self-hating addict; I realize that he did not love his country in any servile way, he loved his archetypes, unseen and turned into obscenities by the vapid popular imagination. He loved that he could find that southern girl, Ruth, and make her more vivid and important than a president in a few glorious sentences; she runs the world as the dark secret you long to hide from and inside. And then, wandering aimlessly on digital highways while working on a memoir section, I find an unreleased song my dad wrote with Ray Charles called “Will I Ever Get Back Home.” It’s interpreted by Madelyn Quebec, with backing on the piano by Ray. They wrote and recorded it in his LA studio together circa 1970. Unlike his semi-patriotic universal love-your-fellow-man ballads, this song is wrenching with an assertively repentant groove, and tells the story of a woman who lost herself in ambition. It could be the opening song for a cinematic interpretation of Baldwin’s story about the girl Friday turned modern comfort girl. I’m out of the wilderness, their child again, their heir, that girl and her foil.

Both Jimmys used universalism to ward off a little scrutiny so they could fixate on their real concerns in deeper studies, more harrowing work that many will never hear or read. I titled a poem “UnAmerican and Communist Inspired” for fun, playfully. I think I read the phrase in someone’s FBI file or police report, maybe one of theirs. I never swore on a bible that I loved this country but I do in loving them or you, it’s what you say when everyone is in trouble and needs to be comforted by her own worthiness of love or fantasies of it in loveless era. As a child of great propagandists, a real lovechild, if you catch me professing unconditional devotion to a nation-state, gracefully or wearily de-cohering, that’s not me. Promise to look for the real me in notebooks and rehearsals—when the war is over look for me.

I have to check out more of your father's music...

That's last line. "Promise to look for the real me in notebooks and rehearsals—when the war is over look for me." Perfect ending