Bereave the Hype

On Kendrick Lamar's GNX and the formulaic worship of emcees from the greats to the disgraced

We no longer dreamed of telling the truth — James Baldwin

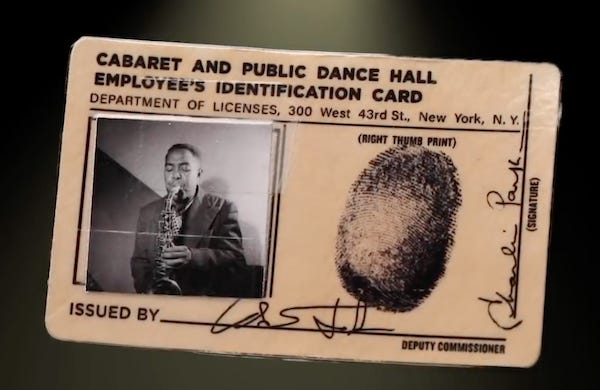

Hip-hop emerged during the summer 1973 in the spirit of collectivity and collective improvisation, and haunted by the spirit of what was commercially labeled jazz music and had dominated the previous several decades, despite its most advanced practitioners rejecting the title ‘jazz’ or correcting it: black music, black classical music, nigga music. Commerce domesticates the black creative spirit; brands sell better than ideas that refuse to be tamed or contained, and record labels who fund studio time, production and distribution, demand that even recording artists adored for subterfuge pick and sustain a genre affiliation. Hip-hop was the new bebop and the star-making machine needed luminaries,and leaders within the form, and nominated them, often by signing them in impressively cohesive groups. Like so-called jazz came up through bands, initially big bands and swing before the war efforts and wartime economy forced the closure of large ballrooms and banned dancing with cabaret laws in New York, where jazz innovation was concentrated at the height of the genre’s popularity, turning the form more reticent and appealing to the cerebral or hip and disaffected white intelligentsia who enjoyed standing at a diagonal against the walls of small smokey clubs, maybe on a good drug or mimicking the effects of using, while witnessing aggressively sophisticated and deeply erotic molecular revolution through improvised black sound. The music cooled, audiences that had once had to participate and find their own rhythm to accompany jazz standards with their bodies, could now attend venues expecting to be entertained, and feeling entitled to idle spectatorship.

The political organizing and revolutionary ideologies that dominated the 50s, 60s, and 70s, before backlash against the Vietnam war, alongside state sponsored ambassadors for dissociation with hedonistic sex and drug use, helped usher in the hippie and psychedelic movements that helped break jazz out of its stupor of cool. Timothy Leary is said to have courted black artists to add glamor to his research— Mingus spent time with him in upstate New York, and Leary once attempted to convince Thelonious Monk to try LSD in a New York hotel room after a concert, but Monk dismissed the offer. Jimi Hendrix and Betty Davis inspired Miles Davis to switch from elegant but archaic traditional suits to paisley button downs, bell bottoms and platforms that insinuated afro-psychedelia. Those who weren’t intentionally strung out on flower child signifying wore costumes that suggested allegiance to mind trips to stay relevant as style and beauty standards shifted drastically. The afro, first low, then higher than golden crowns, replaced the conk or tidy press and curl. It’s alleged that the Charles Manson case roused that generation from the indulgent free love stupor and brought the hyper-vigilant cocaine-dominated 1980s. And embedded in those caustic re-adjustments, hip-hop was becoming its own eternity and turning the ensemble based music on jazz and soul records from previous eras into the epigenetic foundation of a louder more confrontational music that demanded poetry and storytelling to figure out how to coexist with “beats” the lash, the whip, the backlash against jazz and the natural progression of its syntax through spoken language. Where could black instrumental sound go after late Coltrane, Albert Ayler, Eclectic Miles, without the chants that would ritualize and literalize the protests embedded in advanced jazz.

Groups formed and the diminished spirit of raw ideological militancy relocated into a new mode of band-making: Public Enemy, Digable Planets, Wu-Tang, Tribe Called Quest, Pharcyde, The Roots, Mobb Deep, Run-DMC, Fugees, OutKast, Gang Starr, De La Soul, The Sugar Hill Gang, Brand Nubian, Slum Village—before the singular solo emcee became the most coveted asset in hip-hop, it was ensemble music, a space of sharing, sparring, trading verses and mythologizing crews of poets and producers who came up together in cyphers and were virtually inseparable creative partners. But the entertainment industry functions better with dysfunction, singular cultural heroes who can be martyred or lauded alone, alienated or surrounded by support contingent on the whims of fans and the market. This sense of trust and collaboration that had made hip-hop what it was, was dismantled so gradually that it’s not difficult to forget it ever existed or minimize its eminence then and how it might have been so easily dismantled (through precise contracts, the shrinking of a vast set of principles into narrower plots of private property, the taking of ownership over artists in increments as if they were land and territory until those artists grew terrified of breaching tradition and losing everything). I can’t think of a thriving group in hip hop today, but I can count several solo emcees obsessed with and foiling one another in search of the same benefits their profession used to derive from forming cliques and ensembles.

—

Here’s where Kendrick Lamar’s just-released GNX enters the hip-hop epic for me, from a lonely dark alley between the dressing room the studio and the stage, longing for accompaniment, a peer he can trust and settle down with to discuss praxis, but shrouded in hubris and resentment of those peers for valid, sentimental, and inflated reasons, and forcing himself to court tension over alliance. I am bored with the aromantic courtship between amorous enemy-emcees. I’m hyper aware of its desperation, how it indicates their need for real muses, and renewal of the passion that has long been dampened by the duties of fame and self-agrandisement.

From the first track, with its decadent singing that almost tricks us into thinking we’re on a path to interiority with dimension and reach, we get preoccupation with reputation, bitterness, and a hook so half-heartedly inspirational it feels like mid backpack rap layered over a would-be reanimation of now played-out beef. The contrast between “fuck everybody” and oversimplified God-got-me reassurance, both of which clash with the gradiosiity of the vocal hook, feels like being dragged into a movie you realize you don’t actually want to watch, a temperate sequel trying to extort a franchise that didn’t need expanding. And using Jack Antonoff as the staple producer who appears on every track. Without the presence of the classic rap group as archetype, beefing is the only tool emcees have to collaborate and feed off of one another. Admiration, openly declared, is a liability and out of the question. Let me be lonely, they scream. It’s a little alone. By the second track, with renewed cynicism, I’m a finding the open hostility blasé, redundant and hyper-masculine in a way that turns it puny, petty, and codependent on an identity it should have outgrown. The third track “Luther” is one of the album's more beautiful veers, because it romances something other than sorrow and anger, it attempts to access real love, and there is a collaborative element. Sza forces tenderness to the other side of the curtain, drags notes and sings in cursive, but lifts the curse of enmity that prevails on most of the album.

We go right back to coronations though, the predictable hook I deserve it all and threats I’m crashing out right now, no one’s safe with me in the middle of a rage-rant about why Drake is not the G.O.A.T. and doesn’t deserve to be. We know, the re-iteration is a little nauseating. We have established this. Drake’s image is, in effect, dead, and he’s a zombie who also happens to be the most-streamed hip-hop artist. Kendrick holds this prostrate and attacking tone throughout GNX nonetheless, vacillating between wholesome promises to maintain good intentions in his verses, and a deranged fixation on taking down and delegitimizing all competition, what they talkin’ bout, they ain’t talking bout nothing. By the end, despite some stunning interludes that only arrive through surrender to love in the presence of a woman who ultimately turns into his pen so he can bear it without an excess of vulnerability, as on the final track “Gloria,” obviously named to echo glory, the emcee’s first and most enduring muse— I’m left with the feeling that I’m witnessing a great artist and a great form, submerged and undone by the weighty residue of his ego. And I’m no longer even rooting for him to outrun it; I’m praying the genre outruns him and his enemy-cronies and reminds them they are grown men writing one another poems, in love with one another and the form so intensely that they are forgetting what love is, how it requires more strength than cruelty to uphold.

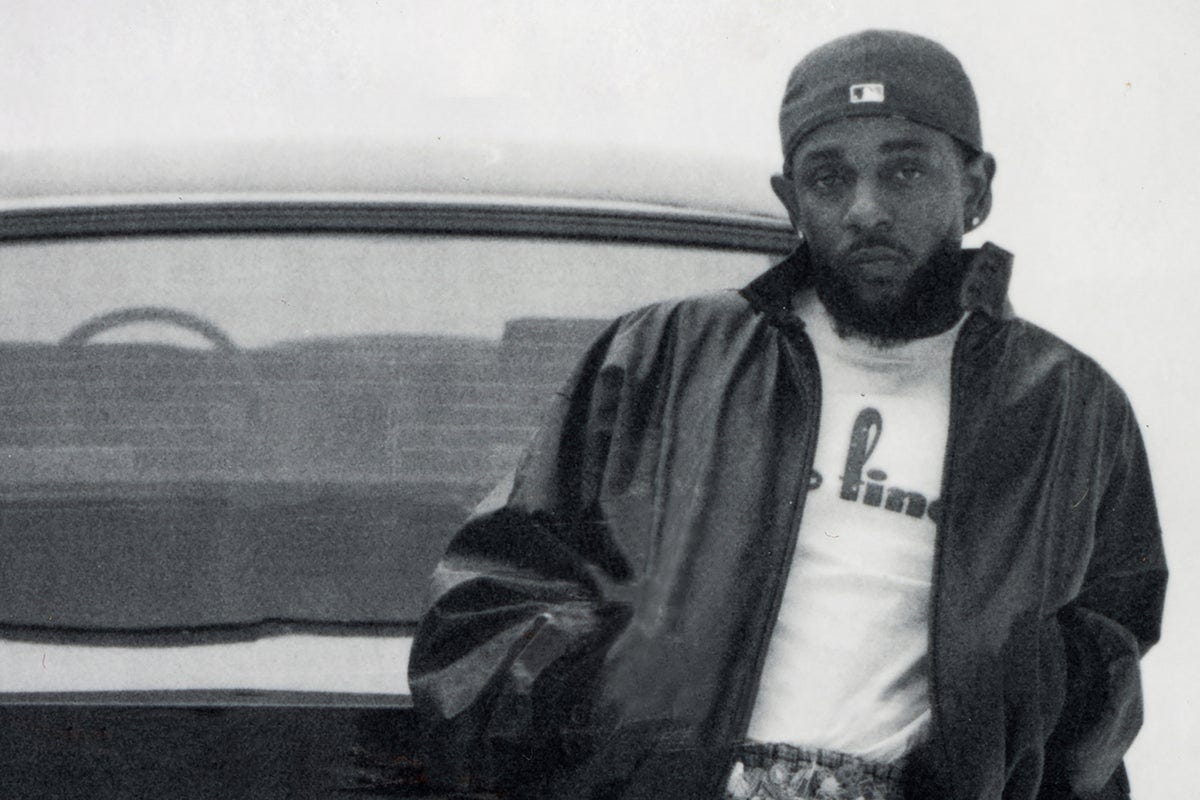

This long embrace of pain, masochistic, hedonistic, inconsolable, relentless, this twelve-track declaration of I must use my pain to create myself , following a summer of identical statements, lands for me as a cautionary tale against doing exactly that. It’s self-effacing to hold a grudge for too long. These men yearn to make amends but are too proud to admit it; they understand one another better than anyone else, and needing a villain this badly is like needing a family, a brother, mother, father, lover or friend to reach out and say I understand you, I accept you, I am just like you, let’s form a group, let’s run off into the sunset reciting sonnets to one another. I don’t think this is the effect Kendrick wanted to have on a fellow poet, but this is what I see when he stands in front of vintage vehicles in the black Air Forces and tries to scare the hoes (Drake)— a pain body running out of space to bleed, a toreador depleted of red flags. Or a celebrity who wants to be a poet in peace but has no sincere peers or heirs who he hasn’t turned against him by writing his love ballads outside-in.

I think, at fifty, this genre, bent on youthful arrogance and real street philosphizing, needs some of the incoherence of free jazz for its finale-ing. It’s been literal for so long, (there was a moment of mumbling but about the same 5 things it’s literal about), now maybe it’s time to stop telling stories and start burdening language with the unsayable utterance. We are due for the baffled late work of writers who know everything must go but don’t intend to sell it out, so have to alchemize it into the next movement, the yet unheard atonal unraveling of everything it once was. These stranded soloists have said all they can in direct address, and most refuse to talk about politics outside of politicizing their shared pathologies. Their heroic next act would be to reinvent language itself before there’s no difference between what Kendrick calls on GNX, the one that’s a coon and the one that’s being groomed.

My God. I haven't read something like this (so scintillating, so precise) in a long time. Your prescience is palpable. And this, like the best of free jazz, is like a code: anyone not in the know wouldn't have a clue what to make of your thesis. But I see it. And I wish some of these artists would accept it, too. Because you're right... beauty awaits beyond the bitterness, the commercial exploitation, within us. Bonus: thank you for mentioning Albert Ayler. A favorite that goes unrecognized often, I find.

This is a very interesting piece, but I don't know if it is accurate to call Kendrick a "stranded soloist." Nearly every banger on the album includes at least one, at times multiple, Cali-based artist from Gen Z, and heart pt. 6 is a story about his come-up journey with TDE. While he is distancing himself from his peers at the grandest level of the industry (Drake, Wayne, Snoop, J Cole), there is a clear return and reconnecting with LA as a city and scene in this album, building upon the current regional sound of LA hip hop (and advancing it too with experimental flows and production). So I don't really see him as this isolated artist, and if there is anyone I wanna see taking a victory lap this year, it's Kendrick.